Mouse Trap

Rats in a maze – fiction by Nick Compton

Bachelorhood didn’t suit Jake. He had an empty fridge and a cupboard full of mice. He’d hear them at night. Not just a few, but bloody hordes of the little bastards. Loud as a herd of elephants. Lying awake in bed, thinking of her, he’d listen to them run riot throughout his little hutong place. It was worse when they’d get into the drawer filled with plastic bags he used for the trash. The scratch and swish as they rifled through them had an air of desperation that panicked him much more than their secret scampering. When he told his landlady, a fast-talking barrel of lava from Sichuan Province, she laughed and waved him off. “It’s an old Beijing neighborhood,” she said in an explosion of accented Mandarin sand-blasted by years of chain-smoking full-tar cigarettes and screaming at her husband. “Buy a glue trap.”

One night he’d forgotten about a cookie in a little paper pouch he’d tucked into the side pocket of his backpack. As he closed his eyes, he heard what sounded like an excited kid tearing into a brightly wrapped present on Christmas morning. He popped out of bed and grabbed a slipper, sneaking to the top of the stairs that separated his lofted bedroom from the vermin below. It was too dark to see clearly, but he aimed for the bag and fired. Upon impact a fat shadow scrambled away, leaving a trail of crumbs and a greasy turd in its wake.

He slept that night with the lights on, certain that his face would be gobbled up in the darkness otherwise. When the sun rose and he hadn’t gotten more than a few minutes of jagged sleep, he decided he’d had enough. It was a Sunday and he didn’t have work. That was good. He wasn’t catastrophically hung over, which was rare for a weekend and also good. Down the narrow alley from his house, there was a mom-and-pop store that sold cold bottles of Yanjing, a mountain of luridly pink, finger-sized sausages that were wrapped up like cookie dough and made of god-knows-what, and an assortment of candies, hardware, and household goods. He thought they might have glue traps.

The proprietor recognized him and greeted him with a smile as he walked in. “American friend,” he said. “Too early for a Yanjing?” Jake looked at his watch. It was barely eight. He considered for a long second before refusing. He wracked his brain for rat-trapping vocabulary that was glaringly absent from the dialogues Li Peng and Wang You held in his Chinese textbook.

“I’ve got a problem.” He said. “Mice. Do you have the thing? The thing I need. I want to kill them.” He sounded childish in his exasperation and he knew it.

The proprietor was bemused, rubbing his chin and chuckling while Jake struggled to express himself. He got up from his seat and reached behind a bunch of hanging mops to a shelf near the ceiling. He pulled out a flat cardboard box and handed it to Jake. In the fashion of so many Chinese goods, the packaging was a jumble of nonsensical English, Chinese characters, and images ripped off from trademarked brands.

“Rat trap. Must-have fashion Accessory,” it said in ugly font above a picture of Mickey Mouse struggling to escape from sticky, white gobs of something that looked too X-rated for Xi Jinping’s tastes.

“How much?” Jake asked.

“It’s nothing,” the proprietor said. “Take it and catch the devils. Just bring them back to me when you do.” He cracked a smile, “My mother-in-law is coming next month and I’d like to give her a gift from my American friend.”

Jake laughed and attempted to place a ten kuai note on the counter but was refused. He liked this shop. Often, clueless backpackers would come ambling through this neighborhood to soak up the romantic, crumbling remnants of old Beijing. They were pure in their innocence, cameras and Lonely Planet guidebooks out but not a lick of Chinese. Other businesses would gouge them mercilessly, charging five times what they did locals for water and candy bars. Here, there was one price for everyone. That mattered to Jake, who found increasing comfort in these small things the longer he was away from home.

***

Returning to his place, the first priority was bait. What do you put on a glue trap? He’d heard somewhere that the best way to catch any omnivore with fur and four feet was peanut butter. He decided it was a safe bet. On top of the fridge where he kept his food and last night’s empty green bottles, he had a jar of the chunky stuff.

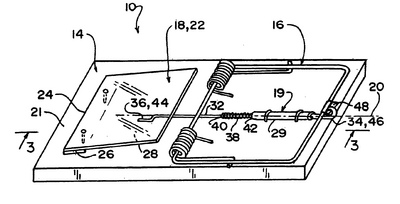

He tore the trap out of its plastic packaging and pulled it open, long threads of glue breaking apart at the fold. He was reassured that he could feel the stickiness. After living in China for the better part of his 20’s, loosening up when he should have been settling down, he’d learned to take nothing for granted. Could be you’d open it to find only dust and let-down. That’s the way China worked. Equal parts build-up and demolition, promise and apology. Real life for Jake, but even now, only just.

He rubbed on a dab of peanut butter with a piece of napkin and thought about where to put the trap. Under the sink, with a constellation of gaps in the wall where the pipes came in and where he’d cleaned up a carpet of mouse shit days before seemed like a logical choice. Setting the trap under the sink and stepping back, Jake felt good. This was something that needed to be done and he was doing it. Something real. He’d catch them this time, he was sure of that.

All of an hour had passed since he’d dragged himself out of bed to deal with the mice and Jake wasn’t sure what to do next. He still hadn’t adjusted to the formlessness of his situation. No commitments outside and no one to come home to. He started with breakfast.

***

He went to his usual joint, where the Beijing grandmas would hover over him, watching him bite into his steamed buns and fried dough, smiling like maniacs.

“Incredible! He can use chopsticks,” one would say while another remarked on the sharpness of his nose and asked him where he was from.

Invariably when he’d say America, they’d nod knowingly and give him a thumbs up.

“Your Chinese is so great,” they’d say, no matter how badly he scrambled the delicate tones.

It was the soft, high syllables of Mandarin that were toughest for him. He spoke in forceful, short bursts when he should have let the words dip, rise. His first language instructor had told him that learning Chinese was like studying ballet; graceful, melodic, flowing. She said German and English were languages that could be conquered. Forceful and unapologetically muscular, sentences that were growled instead of sung. Chinese wasn’t like that. It was finicky, afraid of confrontation. You couldn’t conquer Chinese, you had to court it, dance with it. And even now, after close to a decade, Jake stepped on its toes, the kid at prom who scores a slow dance with the class queen only to tear her dress and set her crying.

***

After breakfast, Jake returned home to check on the trap. His landlord was in the courtyard, sweeping and watering plants.

They nodded at each other and she flashed a half-sincere smile. The same smile car salesmen and stockbrokers use when money is at stake.

“I got the trap,” Jake said. “Put peanut butter on it, under the sink.”

“Very good,” she said. “It’s an old Beijing neighborhood, you know …”

The first time he’d looked at the place, she’d been there to show him around, bragging about expensive new air conditioners, a king-sized mattress and a shower with pressure so intense she boasted it’d blast the corruption off a provincial official. But, whoever renovated the place had done so half-heartedly. It shined on the surface, but below that, like so much of Beijing, was superglue and cheap plywood. Tiles were left unsecure, there were gaps in the wall, plastic pipes that leaked and a strange sewage smell that seemed to permeate from the ground to engulf the whole place in Ming Dynasty stink.

“Yes. Will let you know if I catch them,” Jake said.

“You will,” she said, distracted now by her sweeping. “Just be patient...Those creatures are smart, you know. Add some sunflower seeds to the trap. Beijing mice like sunflower seeds.”

Jake nodded. He wondered what Sichuanese mice liked. Or mice in Shanghai for that matter. Somehow he expected Beijing mice to be grittier. Smog-breathing, gutter-oil soaked tanks. Hardy in the face of famine, instant noodles over foie gras. All but indestructible.

He walked inside and went directly to the sink. He opened the cupboard door and found that the trap was closed. He was careful as he reached to open it. The last thing he needed in Beijing was a rat bite. He imagined the vermin here were riddled with super parasites and other uniquely Beijing bugs that put their brethren in Delhi and New York to shame. Get bit by one of these bastards and after a few days your hand would melt into a black-green puddle of goo. He didn’t need that.

Looking more closely, he could see that the trap was closed flat. No hump in the middle or tail hanging out the side. He poked at it, moving it just enough, waiting for a squirm or a squeak. He heard nothing, so he slid it towards him from the top cover. He pulled it open slowly. In the center was a black circle the size of a dime that the box claimed was a “smell core” wafting out a scent that mice found irresistible. The smell core was there, but the peanut butter was gone. Clean gone. Not a smear or a smudge left.

Jake shook his head. His glue-board soup kitchen was officially open, serving charity peanut butter to Beijing’s vermin for the past two hours. He wondered if the glue was at fault, so he poked at it with his finger and felt the resistance as he pulled it back. Damn sticky. Maybe if he positioned it better. Buttressed in the corner, a fortified position. That would do it. Round two, he thought, reaching up to his fridge to get the jar of peanut butter.

This time he didn’t use a napkin, just dipped his index finger in the jar, fishing out a healthy scoop and smearing it on the smell core. He took his time setting it down. In the corner of the compartment, shadowed and enticing. Rats, eat your heart out. One helluva trap.

***

Now, he could begin his day. He went back to the alleyway store, reached in the back of the fridge where the best Yanjings were and grabbed a couple of cold bottles.

“How’s the mouse hunting?” The proprietor asked, as Jake sorted out his change.

“I treated him to breakfast,” Jake said. “Too smart for that thing, maybe. I just put more peanut butter on it and am waiting.”

“Nothing wrong with that trap,” the proprietor said. “It’s a good trap. The glue’s good. You’ll get him.”

Jake nodded and motioned for the bottle opener hanging on the wall behind the counter. The proprietor knew. He reached behind him and popped open one of the bottles.

“Drink and be happy,” he said, handing the bottle back. “It’s Sunday. The weekend. A day to rest.”

On the walk back, Jake drank the bottle. Chinese beer had grown on him. It was ricey and light on booze but had a certain, captivating funk. A skunkiness that wasn’t as much offensive as it was endearing. It cost about 50 cents a half liter and since she’d left, Jake drank it whenever he wasn’t doing anything and other times when he was.

He placed the empty bottle on the street outside his door. It was worth half a kuai, someone would come by soon to snatch it up. Walking inside, Jake didn’t want to check his trap. That would jinx it.

He idled away a few hours, drinking beer, contemplating the idea of laundry, deciding it could wait another week. He surfed the Internet for nothing in particular. Checked his email, looked at his phone, watched YouTube videos of news anchors messing up. Then, from his sofa, he heard a rustling under the sink. It was unmistakable. Something was struggling in the stickiness; he could hear the squish-squish, like a kid running through a dried puddle of spilled coke. He rushed to the cupboard door, yanked it open.

Nothing. The peanut butter was gone. He could see five-toed footprints and a stream of liquid. Mouse piss? The smell core had been gnawed.

Unbelievable, Jake thought. The audacity of this little bastard. One more try, he thought. This time, the trap hadn’t closed, it was still standing tall in the corner. That was a good sign. Maybe even auspicious. He reached up in the cupboard over his sink where he had a bag of oatmeal and some Chinese nuts that looked like almonds but tasted bitter, like apple seeds. He decided that this time, he would put on just a little bit of peanut butter. Not on the chewed-up smell core, but right on the glue. Then he would stick a few of the bitter almonds in the peanut butter. That should do it, he thought. The mouse will struggle so much to get those little nuts up from the stickiness that he’ll collapse the trap and be in a world of trouble. A sweet little hammer tap to his mouse brain would finish him up and then Jake would take the whole thing out to the trash. Clean and tidy. Maybe even fun.

He positioned his reinforced trap in the corner again. The third time. That was the charm. Maybe the trick was waiting, he thought. He couldn’t jump the gun. No matter what he heard, he wouldn’t open that door and check the trap until the morning.

The day went by quickly now. Jake was thinking about the mouse.

If this didn’t work, what was next? He ate noodles, had some more Yanjing. Watched YouTube. The sun sank and night came. After a few hours, Jake decided to go to bed. He wasn’t particularly tired, but he wanted tomorrow to come. He wondered if he’d have the heart to kill him once he saw him. Stuck. Harmless. He wondered what kind of squeak he’d let loose when he realized he was trapped. And would it matter? How many of them were there? How long would it take? He had to try. He decided it was a good thing. He was a long way from home and what mattered to him right now were these mice. They were pests, bothering him. A responsibility he didn’t need. Not here.

Falling asleep now, in that foggy middle realm somewhere between dreams and reality, Jake heard a rustle. Loud as Beijing. It was coming from downstairs. He’d caught him. He was certain of that.

But he was in no hurry. He was comfortable just then, falling asleep. He’d check tomorrow.

Tomorrow, he said to himself, drifting off to sleep.

Tomorrow.

•

Nick Compton lives and works in Beijing