The Devoured Man (part two)

A different kind of zoo – Josh Stenberg's story concludes

THIS STORY FIRST APPEARED IN HALITERATURE

Back at the museum building, Vitaly slunk off without saying a word, clearly embarrassed at how far from bovine the tigers had proven. The guide, herself frightened witless, told everyone to keep calm. She could not be blamed for the incident, and though the director cuffed her on the head out of sheer frustration when he emerged from his office, gazing uncomprehendingly at our terror like a fruit bat in sunlight, I do not think her job was ever in danger.

The director then delved into a strikingly quick and unperturbed general address of sorrowful farewell, urging us to return on a more propitious occasion—incidentally, they had successfully hosted many weddings.

Strangely, it was the middle-aged businessman who was now sobbing, though the girl could be heard softly to remark, “You should be glad you saved the money….You know, that kid did it on purpose, so no one can be blamed. And for sure, that’s something you don’t see everyday. Though I do think—if you had only sprung for the goat a little quicker— but you will be so obstinate, Piggy.” Meanwhile, responding to a hysterical woman who seemed to think it likely that the tigers, having picked one of us off, would now storm the museum walls and engulf us one and all, the manager assured us that this sort of thing had never happened before, and could never happen again, that it was so very impossible that it had scarcely happened just now, either. It was implied that his poor tigers had been cruelly misused for the boy’s egotistical deathwish. He divagated: they would try to prevent the casualties even of future self-annihilators, perhaps they would have to consider windows that did not open, or were too small for people to fit through. He wouldn’t stand to hear another word said against the poor creatures. At his words, even I had a confused feeling of pity for the tigers, as if they had been slandered.

That was now definitely all; we were dismissed, each visitor upon egress collecting a little envelope—supposedly the ticket refund, but much too fat to be only that. The flashy girl, rudely opening it, immediately turned back, crying, “You must be kidding, director…” and began coquetting with him about the amount. “I’m sure you don’t imagine this is quite enough to stifle the interest of my friend who works for the Heilongjiang Times.”

“I know the head of the municipal propaganda department, and am well-acquainted with all the local newspaper administrators. Unless you want to get your friend in hot water, I suggest…besides, I’m sure you understand that these envelopes are merely a courtesy, a small apology for the unfortunate circumstances.”

“Of course, of course,” said the businessman, recovered from his wailing and managing the circus trick of smiling at the manager while scowling at the girl.

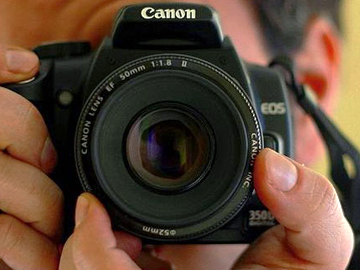

I tried not to let my excitement show, as I too headed towards the exit. I couldn’t wait to get to a computer with the new, dramatic story I could now file. What a jackpot I had run into, had run into me! If the pictures turned out as I thought they might—before the gore, at the beginning of the attack, it was best not to scroll through them just yet— I could even be in the running for those photo-of-the-year kind of things. I’m not saying Pulitzer or the NPPA awards didn’t cross my mind, though that kind of thing seems usually to go for war pics and hurricanes and African babies.

But as I headed towards my envelope, the guide whispered something in the director’s ear. His generous smile conveyed to me that I should feel honoured to prove worthy of his attention. He said, unctuously, “Let me see your camera, sir.”

“What for?” I asked.

“Photos taken during visits to the Tiger Park are property of the Tiger Park. This is the regulation,” he said, though it was clear that the regulation dated from seconds ago.

“Nonsense; I paid for the camera ticket,” I said, fishing for the stub and showing it to him, “The photos belong to me.”

“The circumstances were unforeseen.”

“And the ticket was expensive.”

“Do you know who I am?” he said, tired of the conversation and skipping right to the gentle menaces. In a low voice, he went on, “Do you know how difficult I could make things for you? I don’t want any photos like that on the Internet.”

“I have every right to—”

“Show me your identity card!” he said, now imperious.

I said, “Fine, then. Just fine!” and produced my dark-blue American passport. I have always laughed at those Americans in movies who say you can’t do this to me! I’m an Ame-e-erican citizen! But I confess that on occasion it can produce quite the effect. At that moment, I felt more than usually grateful to George Washington for thinking we might be better off independent. The director’s face fell, and he swore, and he called over the guide, and they conferred while I stood, impatiently waiting, wishing I could go through my pictures and see whether I really had discovered gold.

The guide said, “But you’re Chinese. You’re born in Guangzhou. It says here.”

“Yes,” I said, “I was born in Guangzhou. But I’m still American. See here. Nationality: USA. Got it?”

“But you are Chinese,” said the general manager, relieved. “Now, listen. We kind of got off on the wrong foot. But I’m sure we can clear things up. I haven’t introduced myself yet. I’m Zhang Yuanxi, board member of the Heilongjiang Association for Natural Sciences and the Executive President of the Heilongjiang Tiger Park. I’m also—”

“It’s very nice to meet you.” I said, taking his business card with both hands and making a random inclination, some distant debased descendant of an obeisance. I have sometimes found that it mollifies these senior guys to use their vanity as a defusive force. They’re used to dealing with Chinese journalists, and assume that you’ll print more or less what they tell you. Of course, in my articles they usually end up as strawmen or immaterial footnotes. “A senior civil servant responded to the allegations with a comprehensive denial.” That sort of thing. I said, “Perhaps you have time for an interview?”

“Of course—please tell me your phone number, and what hotel you’re staying at. Or are you staying with family?” I almost fell into the trap by answering indignantly of course not! I’m staying at the Sofitel, but stopped myself in time. “I’m afraid I forgot my card at the hotel. But I’ll give you a call. Then we’ll set a time that’s convenient for everyone.”

My editor didn’t pick up the phone—it was too early Stateside for her to be in the office—and I refrained from leaving a message. There was no question that she would be thrilled by the turn my story had taken. Scandal and devourings rate even higher than endangered species. Sometimes luck is on your side. Sometimes it feels briefly as though there was an account you can draw on in the universal bank of good fortune.

By early afternoon, I had passed from self-congratulation (as if witnessing the incident were somehow to my credit) to reflection. It would make the story much more attractive if I could get a human angle, speak to the family members, include quotes of anger and sorrow and blame. I kept the TV on to see if the incident might appear on the news, to no avail. The park director being a high official, and the victim by all indications a lowly schmuck, it seemed likely that the story had been thoroughly squelched. I racked my brains for friends or acquaintances I might be able to turn to, but I could think of no substantial connections with local newspapers or functionaries in Harbin. And if the story had already been throttled by the higher-ups, I was unlikely to get any help from any variety of stranger.

It was time for some good old American knowhow. Thank goodness I knew all about daring journalistic tricks, having seen them on TV, like what that feisty Lois Lane did, and the chick who hung out with the Ninja Turtles. I returned to the hotel, put on sunglasses and gelled my hair in the imitation of boyish Chinese chic, and changed into some clothes I bought from a stand in the alley behind the hotel, capping it all off with a beanie featuring Astroboy. I looked tasteless and awful, and I supposed that it was an approximation of credibility, of young Harbin chic chicanery.

At the gate of the tiger park, the old grizzly in uniform said, “The park is closed today, for renovation.”

“I’m the cousin,” I said, trying to look mournful and disguise my Cantonese accent, “The cousin of the boy who…you know. Is my aunt here yet?” I was in luck; he nodded warily, then let me through, pointing at one of the death-beige buildings clustered around the museum. In a flaking antechamber with pictures of tigers cut from magazines and pasted on the wall, I found an old couple staring frontally, blankly, as if prohibited from speaking or touching each other.

“…You’re the victim’s parents?” I asked in a hasty undertone.

“It’s an outrage! You’re to blame!” yowled the mother, popping up, acceding directly to her rage. She was broad and leather-faced, and I was struck that she should have produced anything as trim as her son had been. “Why couldn’t you take the simplest precautions—he was—”

“Sh, sh. I’m on your side. I’m Chinese-American, a journalist.”

“What do you want?”

“I want your side of the story. I want to know how you lost your son. Give me your phone number and I’ll give you a call.”

After a moment’s delay and the repetition of my request, she gave the number with willing bewilderment. A secretary arrived to call them both into the director’s office, and from her look of puzzled suspicion I decided it would be best to slip out before I was discovered and detained by further minions of the tiger park.

I had felt certain that the human material would clinch the story, would provide the necessarily poignant background. But the interview, which took place the following day, was disappointing. There was very little to tell. The young man had been severely bipolar—his mother pronounced the word with alienation, as if the entire disease had been imported from a foreign language— and his condition had never been treated. They hadn’t had the money, and the prospects for cure had been negligible. So it had festered. He had lived at home and talked often of suicide to his mother, who pretended not to hear. He was fired from every job after a few weeks. Normal girls would not go out with him. For whatever reason, he had a longstanding fascination with tigers, and commuted to the tiger park on a monthly basis, to watch them eat. This habit had upset them, of course, but there had been so much in his behaviour that was upsetting. It hadn’t stood out; they hadn’t felt it as a warning. Who could think so far, into such perverse corners? The tigers! Who, these days, has doom conveyed to him by way of tigers?

His mother, calmer now, with carefully arranged hair, spoke in a stoic tone that admitted almost no emotion; his father was silent, except when he grunted in what I presumed to be accord.

But when she came to speak of their interview with the park director, her husband suddenly seemed to wake up, and announced, “Don’t—don’t— we agreed.”

In response, she flared up. “We agreed, did we? He threatened us. I have a right to tell the man! This was my son! I want everyone to know! In an American newspaper!”

“I understand: you want them to know how you lost your son.” I said.

“Yes. But not just me…The last time this happened—”

“It’s happened before?”

“Of course it has…You can’t keep eight hundred tigers in a city without the occasional accident, or suicide. Animals get out. Tigers eat people. It’s what they are. And the last time it happened, and the time before, the families got ten thousand yuan.”

“As compensation?”

“Of course, as compensation…But it’s not about the money, you know, it’s the principle.”

“Of course.”

“But because Dongdong was mentally…troubled—they’re only giving us eight. They said six initially, but I wasn’t going to have it. Why should Dongdong be worth less, just because he was…unhappy?”

“You shouldn’t have said that,” said her husband, “We took the money. We took the money, and promised not to say anything.”

“That fat old man doesn’t read English, anyway!” said his wife, “He’ll never know what this guy writes. You won’t write in Chinese, will you? But I want the world to know what happened to my Dongdong, and how they treated him. Why should he be worth less? When I think of what was…what was…”

“What was left of him…” said the father.

“It just turns everything inside out…you saw, it did you? Is that what you said? So you were there. You saw it…Did he…?”

But she couldn’t think of anything to ask, because the questions about the recently dead were removed from her. Obviously Dongdong had breathed nothing in the way of last words, and she already knew that it must have been over very quickly. “Tigers break the neck right away, usually. Not like cats. Tigers don’t play with their…” I said, wholly ignorant of the question, but wanting to leave behind some stupid article of consolation. How quick was quick? How much suffering was not much?

I left before she had the opportunity to break down entirely, and gave my number in case they remembered any other circumstance that might seem important. Some snippet of a story. You say these things. You leave a number. It’s something you always do, as a matter of course.

I spent the taxi ride back calculating how much eight thousand yuan was in US dollar terms, since I would need to put the conversion in parentheses in the text. The lower it was, the more amazing it would seem when included in the article. The price of a human life in Harbin.

From that starting point, my thoughts wandered quite logically to the question of my own remuneration. I began to wonder what I would get paid for the article. If my editor wasn’t willing to shell out enough for a story this sensational, I could shop it around; that was the glory of being freelance, you could bargain when you finally got a hold of something valuable. When you have obtained a little chunk of the lucre, of the reward which is always about us, in which we are floating, the misfortunes of others.

I tried my editor again, hoping she might name a preliminary price just based on the majesty of the story. I mean, the guy got eaten in front of me. And, hoo-boy! The pictures. But I still couldn’t get a hold of her.

The phone rang late that night, while I was in my hotel room bath. Seeing a Harbin number on the cell, I expected the victim’s parents, but the voice on the other end was oily and lubricated: the park director. Dongdong’s mother must have given him the number—she was apparently grieving so universally that she didn’t care who she played off against whom. Perhaps it had earned her another couple of thousand yuan. I couldn’t really begrudge it. Because I’m just that noble.

“Hello! I’m very happy to get a hold of you! I was hoping you’d come to my office, for that interview. I’m sure we can work something out.”

“Yes; as I said, I’m perfectly happy to meet for an interview.”

“Wonderful.”

“But you do have to understand that my code of professional ethics means that I report things impartially, as I see them, according to whatever the evidence suggests.”

“Of course, of course—I just want you to hear my comments. So that you can write your article impartially, without interference.”

We agreed on a time the following day. I decided he had decided it would be a lot of trouble to bump off an American citizen, and felt comfortable that nothing more dangerous than menaces and bribery were being prepared.

First they gave me tea; only later liquor. A whole thicket of niceties had to be observed, during which I commented on the beauty of the tiger park, and he claimed, quite absurdly, to be an admirer of my work. The poor bushes were thoroughly beaten.

Then he summoned a secretary and had her deliver an envelope from a desk into my hands. “This is a small token of appreciation for the interest you’ve shown in our humble organization.”

I couldn’t help noticing that it was very thick, much more so than the compensation of the previous day. “Really, I couldn’t,” I said.

“But I insist. Just as an indication of how much we appreciate it when the foreign media send their best and brightest here.”

“I don’t think you understand the way journalism works in the USA. It’s not like China—you don’t pay journalists for writing you up.” He nodded and snapped his fingers, and a second envelope joined the first. “You’ve got it at all quite wrong. I’m bound by conscience and contract to report what I see, and ask the tough questions, even if the evidence sometimes points to…oversights or even…neglect.” With a scowl, he snapped his fingers for a third envelope.

“Do you understand?” I asked, weakly.

“Yes, I understand. We respect foreigners and journalists a great deal. Now give me your camera, and we’ll drink on it. I have some special Maotai Liquor.” He had not quite pulled off the joviality, it carried a nasty undercurrent, like a badly mixed drink. I retained my camera with its precious high-resolution cargo, trying to remain pleasant.

But at the end of the dinner a minion appeared with a new Nikon camera, a luxury article, well outside of my price range. I was surprised that it was even available in Harbin, and said as much.

“Not from Harbin; from Tokyo,” he said, pregnantly. “My son flew there, last night, to get it.”

I couldn’t resist taking a look. Or holding it in my hands. Or trying out the settings.

“Do you like it?” asked the director, with a note of triumph.

“I saw that you called,” said my editor, who phoned when I was dead drunk and wealthy, back at the hotel. “Twice. What is it? Was there some kind of break in your story?”

“Break?—No, no—No.”

“No?”

“No—I mean—I mean—there was an exciting lead, but it didn’t pan out. So, same story as before.”

“OK. So that was all?”

“Well—well—I guess.”

“…OK, well…um…sounds like you’re having fun. Don’t overdo it out there, buddy-boy.”

“No…”

“Then, I’ll look forward to seeing your story by Thursday. And don’t forget to snap an action photo, if you get the chance.”

“Yeah, I’ll get it.”

“The tiger in mid-pounce, you know, aggressive—snarling—pouncing—something like that. A photo with something going on, you know?”

My friend the director forwarded a spectacular shot of a tiger clawing down a cow, from the park archive. The director wrote that I was welcome to claim it as my own. Or I could come back to the park any time and take an action shot of my own with my gorgeous new Nikon, straight from Japan.

•

Read part one here. This story first appeared in Party Like It's 1984, a publication of HALiterature

Josh Stenberg is an Asia-based writer whose work has appeared in various journals and anthologies. He has translated two volumes of Su Tong’s fiction and edited Irina’s Hat: New Short Stories from China