Red memories

Touring a Chinese Cultural Revolution museum – by Jesse Field

Lack of planning, pure and simple, left me with a day-long layover in Shantou, a city in northeastern Guangdong province which is home to China’s only museum devoted to the Cultural Revolution.

There’s something creepy about setting out in pursuit of trauma tourism. Tripadvisor’s top picks for attractions in Shantou include parks, a Teochew mansion, and a ferry ride out to Nan’ao Island for beach vistas and seafood. Why should a newcomer in town for only one day skip these fine locales to see old pictures of Chinese society tearing itself apart? Chinese nationals are justifiably frustrated when foreigners take a one-sided interest in China’s mistakes. The truth about the history of nations and peoples requires multiple contexts.

The trip to the museum is awkward and somewhat difficult, even if you speak Chinese. “Cultural Revolution Museum?” the cabbies repeat the phrase to themselves, mulling it over. They’ve never heard of it. The museum is in Pavilion Park, which as I learn after a pensive drive inland through the dully industrialized Guangdong coast is a former Buddhist temple complex. The restored temple sits next to a small lake with a tall red and white stupa nestled in the hills above.

The park is a temple, a graveyard and an amusement park all in one. Forget josh sticks — some worshippers in the temple wave whole baskets of offerings before the Dragon King and Buddha the protector in his warrior costume. Outside, one can ride boats while loud music is piped out over the lake, or play carnival games with prizes that include tiny caged rabbits and birds. A shoddy castle-like structure erected alongside the temple promises something called ‘Futureworld Thematic Parties.’ Who knows how many of the resident dead were victims of the Cultural Revolution?

There are no signs pointing to the museum, but some of the people working the snack stands know it exists. One man waves me down the road, saying that the cultural relics exhibit is below, in the temple courtyard. “No, he didn’t say cultural relics,” his wife corrects him, “he said Cultural Tevolution.” The man looks puzzled, as if he had never heard the term before. “You’re going the right way, son,” his wife says. “Just keep walking up the road to the top of the hill.” I did, and the sounds of loudspeaker music, fireworks and playing children slowly faded away.

The theme of the museum is the value of historical memory. “History serves as a mirror,” proclaims one stone inscription outside. Another quotes Mao Zedong: “The only way for humanity to cleanse itself of its mistakes is to speak the truth about them.” Sounds nice. But what is the truth? And can it ever really be spoken?

A major exhibit outside the main building celebrates the heroism of Peng Dehuai, one of the military leaders who helped defeat the Nationalists and establish the PRC in 1949. He was struggled against so relentlessly by Red Guard leaders forty years his junior that he is said to have died from a head injury received in his beatings. “No one can hear of Marshal Peng’s story without it bringing tears to his eyes,” reads one plaque.

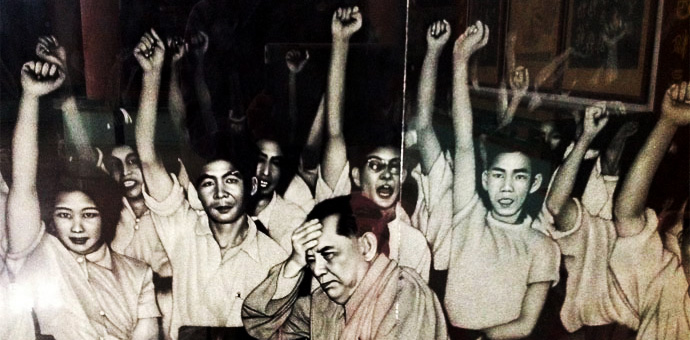

Inside, the display is arranged as a matrix of large text and photography pages that have been electronically etched into stone. Everything is shades of black and gray – snarling teeth of anger, dark-lidded eyes of bemusement and pain. Arms yanked back and up, heads shoved down in “the airplane”, the most famous of the stress positions used. Death by injury, death by suicide, death by execution.

What are the lingering effects of the Cultural Revolution? On this, the museum is silent. A bizarre, unexplained sculpture on the far side depicts a yellow road that runs uphill, folding over and against itself, back down into the ground. A portrait of broken teleology? The whole place reeks of neglect and cigarette butts, oily dust on every surface. Against a black stone wall commemorating the names of the dead, enterprising locals have set up a stand for bad ice cream and warm coke.

They say a retired vice-mayor of the town used his considerable political connections to set the museum up and swore to visit it every year for the rest of his life, but lately threats from the Party caused him to beg off. It strikes me that he state will ignore the museum and what it commemorates until that history dies too. All of the tensions that caused the rupture in the first place will remain unresolved, like untreated PTSD on a national level. One question asks itself above others – could this happen again?

Back down at the temple, the warrior Buddha announces “Dharma protects; the demons will fall.” Little boys swing cheap wooden swords sold at an adjacent stand. Who will the demons be next time? Picking up my pace in a sudden cold sweat, I suddenly want to leave China before I learn the answer.

•

Jesse Field lives in the hutongs and teaches at Peking University Associated High School

This post first appeared at Jesse’s blog here. All photos by the author