White Monkey

Living it large as a laowai performer – by Eli Sweet

I was already a rapper when I arrived in Chengdu in the fall of 2006. I had started rapping in high school, around when I started studying Chinese, and my identity back then was largely defined by those two hobbies. After I graduated college I recorded two hip hop mixtapes, which were released to underwhelming public response. Hip hop had begun to look like a long shot; China seemed increasingly promising by contrast. So at the suggestion of a former study-abroad classmate I hopped a plane for Chengdu.

Shortly after landing, I saw a flyer for a rap battle at a bar called Hemp House. Battle rap was not my forte, but I was not discouraged. I wasn’t sure if I’d even have a chance to participate but I wrote a lengthy chunk of insulting verse nonetheless and rehearsed it carefully. I’d be ready to make my China stage debut if given the chance.

The Hemp House was thronged with young Chinese in basketball jerseys and fake jewelry – requisite hip hop gear at the time. I was surprised by the size and the energy of the crowd and immediately felt self-conscious in my hiking jacket. The vibe was not so unlike battles I had attended in downtown Atlanta. I took off my jacket and bunched it tightly in one hand. I was nervous and giddy.

The battle was hosted by two Americans, one DJ, one MC, but featured Chinese rappers battling in Chinese. I wasn’t prepared to rap in Chinese, but I approached the DJ (Just Charlie) and leaned across his decks.

“I want to rap!” I yelled at him.

Just Charlie eyed me for a moment and called over the hosting MC, Tenzin. He agreed to battle me in English, and before I knew what was happening, we faced off in front of a cheering, if uncomprehending, crowd. Tenzin was a seasoned performer and hyped up the crowd with a call and response approach, which was well received. Then it was my turn. Charlie played the “breathe” instrumental, and I laced it with the lyrical fury I had been cooking up. The verse I’d prepared was loaded with multi-syllable rhymes – I’m the captain of the ship, rapping just to kick the ass of any wack-ass battle rapper in this bitch – and as I started to land them, I gained confidence. Smack him and his clique just for yapping at the lip, this sack of shit, ain’t good enough to practice with. I got increasingly animated. You lack heart and you lack in wit, but see I’ve mastered it, I’ll leave the massacre immaculate. The crowd was stunned by my competence and aggression.

Tenzin declared our battle a draw (he was also judging), which seemed magnanimous. After the show, he and I chatted over beers. He had just finished a nation-wide tour for Coors and was swamped with jobs. I was enthralled hearing about the market for foreign performers. Tenzin rattled off names of cities where he had performed. Then he offered me a paying gig on the spot, the following weekend in Guiyang.

I agreed immediately, trying not to sound too excited. I would go to his office that week and take some promo photos for posters. The office was in a tall building with a bank on the ground floor, and offered a tacit guarantee of future fame. I was being inducted into an exclusive cohort of foreign performers, I imagined. I boarded the plane to Guiyang brimming with grandiose fantasies. Hip hop was taking off in China and I was going to be a part of it.

*

The club in Guiyang is like many of the nightclubs I will encounter over the next few years. Run-down, lurid, yet enticing. It is a dark maze of tables bolted to the floor, hosting a cross-section of the drinking public. There are fun-loving college students, professionals on the binge, and gay men with gel-sculpted hair. There are opportunistic women, predatory men, and waifish ketamine users swaying unsteadily to the music. The usual.

Not that I recognized any of these familiar elements when I arrived. I had rehearsed two songs beforehand, and showed up to soundcheck with a CD of backing beats to use for my performance.

When I offer it to the house DJ, he looks at it like a slice of moldy bread.

“No need” he says. He has techno music for me to rap over. I will rap over the music he always plays, he explains. I hate techno, but I am undaunted.

I perform that night over a pulsing baseline that is anything but hip hop. I try to spit the songs I’ve rehearsed, but the tempo is too fast, and the lyrics dissolve into an unintelligible clatter. Even with a scantly-clad dancer thrashing onstage behind me, the crowd seems indifferent to the performance. When I finish, I am sweaty and hoarse, deflated. I had anticipated a better reaction.

“It doesn’t matter what you say,” Tenzin explains to me weeks later, back in Chengdu. I’m watching him work the crowd at the grand opening of “International Club”. Tenzin is spooling it out, not trying to fill every second of dead air. He is relaxed, with an imperious swagger. He talks to the crowd, singing along to the music and interjecting snappy vocal improvisations.

That’s when it dawns on me. Tenzin isn’t just a rapper; he’s an MC in the traditional sense: a host. He shout-outs the club, interacts with the DJ, and introduces the male stripper and the fire spinner when it is time.

“Watch this,” he says to me. He turns back to the crowd, and starts rapping:

“Blah, blah, BLAH, blahblah blahBLAH.”

I am confused, then amused, then impressed. He continues, ‘blah, blah, BLAH, blahblah blahBLAH,’ just repeating the syllable again and again with alternating emphasis. The crowd is going nuts; no one registers this gibberish as gibberish. It’s all about the energy. Tenzin switches back into English and starts rapping about the fact that he is not rapping about anything. He starts dissing the crowd for their inability to understand, in a friendly way. We toast our beers.

It is enlightening and disheartening. I realize I need to abandon the notion of lyricism; communicating with the audience is beside the point. Tenzin is not just a rapper, he’s an entertainer. The job is to create a spectacle. I can do that.

*

That realization opened a lot of doors for me. There was a profusion of ‘white monkey’ work at the time, and I relished the absurdity. Foreign faces were needed for print ads, TV, and live events, to confer status or quality. A network of seedy talent agents serviced the market, lingering outside foreign bars to collect phone numbers. They offered easy money and put a flattering spin on demeaning work.

That realization opened a lot of doors for me. There was a profusion of ‘white monkey’ work at the time, and I relished the absurdity. Foreign faces were needed for print ads, TV, and live events, to confer status or quality. A network of seedy talent agents serviced the market, lingering outside foreign bars to collect phone numbers. They offered easy money and put a flattering spin on demeaning work.

I gradually got better at objectifying myself. I posed for a department store catalog. I worked the catwalk at a low-budget fashion show in a public square. I cut a promo video for a chair factory. Then I was hired to live in a glass box for a week.

“The Home of the Future”, as envisioned by the real estate company that hired me, was a transparent cube with a modernist couch, a Roomba, and a living, breathing foreigner – me. For the week of the real estate fair I inhabited the diorama, wearing a white terry cloth robe and slippers, and pretended to go about my futuristic daily life as crowds streamed through the exhibition hall, pausing to gawk. A pre-recorded video played on the wall, and I interacted with it as though it were live.

One video showed my purported girlfriend, and we chatted through the screen. In another, I mimicked taking a kungfu class remotely. I communicated with the exhibition-goers by writing on the inside of the glass walls with dry-erase markers. Sometimes children threw candy into the open-top of the glass box. My week spent in the future obliterated any remaining discomfort I felt about putting myself on display. It also paid my rent for five months.

I gradually improved as a club performer too. I didn’t have any qualms about simplifying my raps, and I didn’t mind clowning around on stage for a few bucks. The more I separated my ambitions as an artist from my job as a performer, the smoother things went. There were moments of awkwardness – like when I would lock eyes with a foreigner in the crowd, looking on with derision (or worse, pity) – but I felt that my self-awareness was a shield. I could deflect embarrassment with a knowing wink.

I was working every weekend. When I asked for more money to perform, the agent booking me agreed without protest. Business was remarkably steady but I couldn’t figure out exactly why. Most of the audiences’ responses were tepid at best. The nightclubs didn’t seem to be paying the middlemen who paid us; the money was coming from somewhere else.

Western liquor companies first made significant headway into the Chinese market in the late 90’s and early 2000s, teaching nouveau riche Chinese to drink whisky. It was rough sledding at first, but they concocted new drinks to suit the local palate (most notably sweet tea and whisky) and relentlessly peddled glamor.

Over time they colonized consumer tastes in glitzy big-city clubs – clubs with strobe lights and dry ice, dice cups and metal stools with faux-velvet cushions scarred by cigarette burns. The clubs exacted a price for their cooperation, a kickback on every bottle sold, and free entertainment to help push sales. Brands invested heavily, hoping to gain access to the growing market of middle class Chinese consumers.

By the time I arrived, these liquor brands had begun to bring their marketing magic to second and third-tier Chinese cities. “Brand ambassadors” like me were the tip of the spear in a Chinese marketing charge.

*

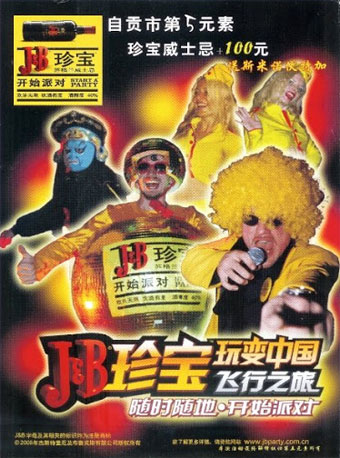

Being Discoball Man is pretty similar to how you might imagine it. It entails wearing a styrofoam disco ball around my midsection, and relinquishing my dignity for the evening. The disco ball goes from my nipples to my knees, and is terribly unwieldy to navigate through the club in semi-darkness. Wearing sunglasses doesn’t help. The ball is covered in tiny golden mirrors, and some of them crack or flake off each time I collide with tables and chairs. With my gold shirt and the disco ball helmet I look unimaginably tacky, but paired with a wide smile, the effect is irresistible to customers. I’ve signed up with J&B’s ‘Start a Party’ campaign, and they have sent me to Zigong, in southern Sichuan, to perform at the Fifth Element club.

The club boss gives off the vibe that he is mafia-affiliated and not totally on board with our vision of party starting. When we arrive for soundcheck, he is smoking and berating his staff. He is skinny yet overweight, affluent yet tastelessly dressed, with dirty teeth and a hint of cruelty. In the afternoon light I see how cheap and sad everything in the club looks. I notice the shabbiness of the wallpaper, the stickiness of the floor, the odor of stale beer – the hollow pretense of glamor.

The club boss wants the DJ to play earlier (or later), he wants the dancers to dance more, he wants the rapper to sing. I am familiar with his expectations. The more I’ve performed, the more I’ve come to understand the limit of rap’s appeal to Chinese club patrons. So instead of rapping, I shimmy and shout, I holler and hoot, and I jump around energetically. Sometimes I freestyle a little. But mostly I wait.

I’m waiting now, in the dressing room, watching the dancers apply their makeup and check their phones. There is a bottle of whisky, some sweet tea and a bucket of ice on a glass table. I am already wearing my gold shirt and pants, waiting until the last minute to slide into the disco ball. The club staff is talking to my handler, trying to decide the right time to begin. They take turns making trips to the smoky dance floor, gauging the atmosphere.

When the club staff signals that the time is right, the DJ puts on my theme song, and I strut onto the stage like the Kool-Aid man. After a few seconds of grinning and waving, the DJ turns down the music and I address the crowd, welcoming them to the event, and repeating our sponsor, ‘J&B’, over and over. I speak with over-enunciation, like a ballpark announcer, and stretch out the last syllable of each phrase.

“We have a brilliant performance prepared for youuuuuuu!” I yell. “Are you having a good tiiiiiiiiiiiiiiime?!”

“Yaaah!”

“I can’t hear you!”

The DJ turns the music back up and I start rapping.

It’s tough to find my feet on the house music, and it takes a minute or two to get into a groove. I spot a bewildered customer, staring glassy-eyed, and I double my intensity, plowing through his gaze with a torrent of syncopated expletives. The crowd is now paying attention; it is time to bring out the big guns.

“When I say HEY, you say HEY. HEEEEY! … HEEEEY! When I say HO, you say HO. HOOOO! … HOOOO!” Call and response never fails. “HEY! HEY! … HEY! HEY! HO! HO!… HO! HO!”

It’s time to start a party. I climb clumsily down from the stage and initiate a conga line with the female dancers. We have worked out the routine in the afternoon – female dancers in front, discoball man behind, so the girls aren’t harassed by customers.

I feel the men behind me – yanking, pushing and pecking at the disco ball as we thread through the club. I go table-to-table, greeting people and taking pictures with them. Shirtless pot-bellied drunks congregate on the dance floor, eager to offer a drink, a smoke or their telephone number. In many small market clubs the presence of foreigners is unprecedented, and the crowd’s enthusiasm is as palpable as the breath of a stranger, leaning in too close to shout something unintelligible in local dialect.

*

“Would the Captain say ‘argh’, or would that be too cliché?” I ask.

It’s mid-2008, and I’m sitting in the lobby of a fancy hotel lobby in downtown Kunming sipping cappuccinos with Captain Dave.

“The captain might say ‘argh’, but he would not overuse it,” he explains.

Captain Dave has played Captain Morgan, the eponymous pirate mascot of the popular rum brand, in official advertisements for years already. He’s made a fortune portraying the Captain, and has flown to Kunming to train me. Captain Dave looks tired. Soon he has to be in Russia for a music festival, a few bar events in Ireland, then back to the states for the start of the NBA season.

It all seems exciting and, well, professional. The heavy red brocade overcoat I was issued was tailored in New York, and I felt a swell of pride as I cinched it at the waist with a red sash, tucking my replica flintlock pistol in at the hip. I appreciated the gravitas required of the role. There was talk of an upcoming brand launch in India, and I was being considered as a candidate. I felt like I had finally stumbled into my destiny.

So I worked the Caucasian Kabuki chitlin' circuit with gusto, going from city to city as Captain Morgan, visiting clubs as well as more intimate venues. Chinese friends celebrating a birthday in a private karaoke room were surprised and confused when I burst through the door, and swashbuckled up to the mic to introduce myself. They had bought a bottle of the Captain’s Private stock, and I was there to ensure that it was an unforgettable night.

I stood in front of a grocery store, flanked by women holding a tray of samples, waving at passersby.

“What is langmujiu?” they asked.

“It is called ‘rum’ in English. It is made from sugar cane. Try some.”

National public radio interviewed me that year, about my life as an expat performer before I was hired to be the Captain. It showed me standing on the roof of my apartment, ruminating on life abroad as I stared into the haze. I was a post-modern beatnik, in my own hazy mind.

It was later that year, in fall 2008, that I first heard about the collapse of Lehman Brothers on NPR.

I was going through my pre-performance ritual, blackening my mustache with mascara and putting on leather spats while listening to a podcast. I grinned with shadenfreude at the mention of “contagion” on Wall Street, tying my polka dot bandana atop my long curly wig. The collapsing banks seemed impossibly far away from Kunming, and the mountains that buttressed it. Hearing news reports of the financial crisis was like watching a distant explosion, certain that you were safely beyond its blast radius. But I wasn’t impervious, just oblivious. Hours later, when I emerged from the club, carrying the treasure chest full of eye patches and sticker-mustaches back to the minivan, it felt like another regular night.

Soon after, my boss in Shanghai told me that my number of performances would be ratcheted up from three to five nights a week – for the same salary. I was sure that this violated our contract and I was prepared to argue the point when he flew to Kunming to discuss it over dinner. He told me flatly that it was out of his hands. Captain Morgan had been pouring money into brand-building in Western China, but it wasn’t seeing profits. Their parent company, Diageo, was reeling from the volatile financial markets, and that meant squeezing more value out of China.

“They want to get more bang for their buck,” he explained. “We’re lucky that we’re still getting anything at all.”

By the time I realized what was happening, the wheels were already in motion. The Captain Morgan campaign was extended another three months, but plans to take it national were nixed due to budget constraints. When I got back to Chengdu, performing jobs were fewer and further between. The booze gigs had all but dried up. Tenzin’s business had closed, and he had moved back to the US. I soon found myself on an auditorium stage at a corporate retreat, performing between a magician and a ballet duo.

*

The next time I make it back to the Hemp House for a rap battle, it’s 2012. I’ve got a nine-to-five job in the logistics industry, and have more or less fallen out of the scene. I’ve performed some since Captain Morgan – in between studying and sending out job applications – but less since I got the office job.

The bar has changed, but not much. It’s packed, and I squeeze into a spot along the stairs, between fans trying get a view of the action below. The battle is part of a regional ‘iron mic’ competition, and rappers from different provinces are facing off. There are tenacious punch lines and intricate rhyme schemes, plus local flavor, self-awareness and humor. Crews are selling merchandise. There is very little costume jewelry. The scene feels more authentic and less derivative of American battle culture than it did years ago.

I spot a foreigner in the crowd below, kicking it with some of the battlers, and I resent him. Seeing him inside the circle of performers makes me acutely aware that I am now outside of it. My mind races to think of insulting rhymes. Maybe we’ll end up battling, I’ve got to be ready to rip him up. It turns out he isn’t a rapper and we later become friends, but in that moment I’m struck with the fear that I’m losing something – a coolness, a spontaneity. I haven’t yet abandoned my dreams of stardom.

I was disappointed that hip hop fame did not materialize for me in China. Even after it became clear that club work was not a portal to stardom, I clung to the idea that it would somehow advance my creative ambitions. I exited the industry without fanfare but I still make rap music in my spare time. The memories from my performance days have hardened into a set of well-polished war stories that I tell to buddies over beer and to colleagues over wine at events for the Chamber of Commerce, where I am now a white monkey of a different stripe.

I still host events, but now I take the stage in a suit instead of a costume, and I toast guests at banquets instead of bars. Baijiu has replaced rum in my glass. I realize my function is not so far removed from what it was when I was performing in nightclubs. I am there to add a little bit of foreign flavor to the mix. And that’s OK with me. I enjoy meeting new people, and I know that when you give someone face you get something in return. It is a symbiotic relationship. Besides, my cheek muscles are well-practiced at forcing a natural-looking smile.

•

Eli Sweet was born in Atlanta and has lived in China for over nine years, where he is the vice-chairman of AmCham SW China. Listen to his music on his Soundcloud here