Shower Business

Last days of a Beijing bathhouse – by Robert Foyle Hunwick

Hong Sheng, qigong master, can perform nude splits on a bridge of cracked tiles in a sauna the temperature of Mount Doom like a man half his age. That’s how some guys like to roll in China: the backslapping, the baijiu toasting, the bonobo displays of power. Beijing’s last old-style bathhouse isn’t the kind of place to worry about stray hairs, clean towels or a brace of someone else’s overripe cherries.

Just shy of a century old, the Shuangxingtang bathhouses in the far south Beijing suburb of Fengtai is one of the capital’s toughest buildings. So far it has survived a republic, various warlords, a full-scale occupation and a bitter civil war, followed by everything the Communist Party could throw at it. It’s fitting that property developers are most likely to finish this place off. A shame – there aren’t many hide-aways where one can escape from decorum so cheaply. Napping, grumbling, smoking and masculine displays are all being pushed out to the suburbs.

Don’t expect, or wish for, much courtesy from the older generation at Shuangxingtang (established 1916). They’ve had it with the outside world and its high falutin ways, and this is their last-chance saloon. Next door to my booth, on arrival, some used longjohns were draped over the shared divide. I had assumed that they belonged to the gentleman dozing in the adjoining stall and ignored the pair, like you would any old man’s underwear. Sensing my presence, he jerked to attention and looked straight at the soiled drawers. “Get this crap out of my face!” he barked.

It turned out he was talking to someone behind me: ‘Little Kim’, barely a day over twelve and in charge of shoveling these old bastards’ shit. Already he bore the look of a portly North Korean dictator, and the thin sheen of exertion on his moon-like face spoke of purges to come. Some day, I consider, this Kim will make an upstanding official or truculent businessman. Or if it goes wrong for him, maybe a career janitor.

That isn’t odd anymore to me, to see an adolescent gofer serving far older, possibly wiser, undeniably more wizened people. This was how the public baths of Rome might have looked in their dingier sections, reserved for the hoi polloi, away from the sophisticated symposia: Down Fengtai, rather than up Pompeii. It turned out I was wrong about Kim – the sly fellow was 17, or that’s what he claimed, enthusiastically smoking on a gold-tipped Hongsha. Despite the obligatory ‘No Smoking’ signs, hunkering down with a brightly colored cigarette is a cherished pastime at Shuangxingtang.

While bathhouse culture still thrive in China, the model is changing in the big cities. Back when indoor plumbing was a luxury, your grandfather might say “the rich go to the doctor and the poor visit a bathhouse.” They were an essential part of the community: people gathering to eat, smoke, sleep, argue, play Chinese chess, sleep, watch cricket fights, smoke, eat, sleep, read the latest tabloid insights, drink, smoke, eat and sleep, all while telling their family they were just popping out for a communal bath. Now the rich are visiting bathhouses in droves, and favour the deluxe rub to the plebeian tub.

Big bathhouses these days are expected at the least to have some upstairs massage rooms, with special services, rotating buffets and flatscreen televisions showing sports. Sweating in the nude, next to a shrewd investor, crooked cadre or blubbery cop, comrades are all rendered equal (there’s less risk of being recorded and blackmailed afterward, too). It costs over two hundred yuan to visit one of new-fangled bathhouses – where hot-spring pools are decked out with fake trees, ornate footbridges, uniformed attendants and fish that nibble on your dead skin – and less than ten yuan to get the full Monty at historic joints like Shuangxingtang.

It’s not just the lifestyle that is dying here – it’s the customers. Places like Shuangxingtang are literally running out of punters. In September 2014, the Xinyuan baths in Haidian district, allegedly built under the Guangxu Emperor, had their doors closed for them by a bulldozer. Well-intentioned local regulations, designed to keep the facilities affordable, had prevented Xinyuan and places like it from increasing their fees enough to pay the rising bills, consigning the business to history.

The Xiong family, who have owned Shuangxingtang for the last two decades, know their shop has its name writ in water. The walls are speckled with evidence of a losing battle with mildew, where the forces of ayi and her mop-bucket are in retreat. Most tiles are cracked or missing around the larger tubs, and the grouting has a giddy, mustard tan that speaks to years of nicotine fug. Shuangxingtang was the main shooting location for the film Shower, which received multiple international awards and “two thumbs up!” from Roger Ebert in 1999. That was 16 years go and all attempts made on the back of the film to apply for World Intangible Cultural Heritage status have failed. The place is doomed, and I can’t explain why.

There are huge, blown-up photographs depicting key scenes from Shower braving every room (I initially mistook them as adverts for the services offered). These are misleading if it’s spa facilities you’re after. Seek out a creamy facial mask, or a soothing peel, and you’ll be met with a polite stare – this is your great-grandfather’s grandfather’s kind of place, no fuss and most certainly no muss. There’s supposedly a KTV upstairs, but I didn’t dare risk it.

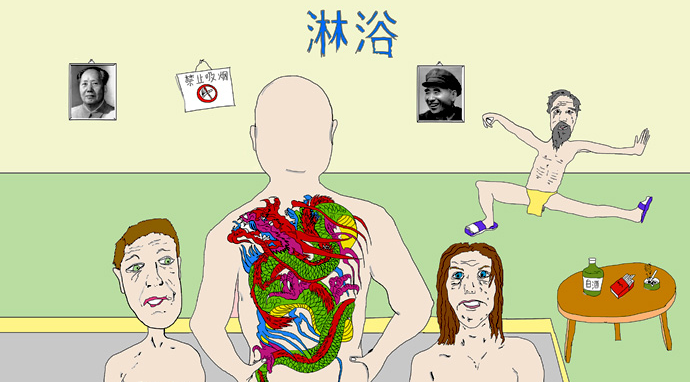

Other than that Mandopop upstairs, not much seems to have changed since the Cultural Revolution. There are still framed, black and white photographs of Mao Zedong and Lin Biao hanging in the changing room, although they’re kept well apart, at opposite ends, in fact, with Mao on the left and Lin on the right – politically correct even in death. Thirty years on, Lin Biao remains the PRC’s foremost traitor and public enemy, so to display his portrait takes indignance, indifference or some merry prankster at work. It’s especially ironic in this context, as he was supposedly terrified of water.

It was past dusk on a chilly winter’s evening when my companion Jay and I groped our way through the neighbourhood, searching for the right bathhouse among an array of identical, dimly-lit alleys. It was six o’clock, so naturally the street was deserted, and there was no one to tell us where we were, nor any landmarks – just row upon row of dingy shops, restaurants and lock-ups selling hubcaps and other motoring goods, plus the occasional, evil-looking karaoke joint. We watched a depressed-looking 30-something hostess in a down coat begin her shift at an ominous Entertainment Complex offering “Massage, Sauna, KTV”, and hoped to God this wasn’t the place. It wasn’t: we had passed it a block back.

Entrance was a cool eight yuan. For another twenty, they throw in a full rubdown (recommended) along with the complete day of soaking. No overnighters, a sign warns – they’ve had trouble with those, and besides, there’s a hotel next door. Shuangxingtang doesn’t see a lot of trade from foreigners and we got the traditional bathhouse welcome: a friendly nod, then an unbridled stare downward. Whether it’s a glance or a glare, other customers rarely hid their curiosity and I chided myself for not offering better entertainment – an elaborate green merkin or ‘Drink Coke’ tattoo pays for itself.

Cigarettes are the preferred currency. One determined middle-aged man, gripping his lit cigarette through determined teeth, absent-mindedly soaped himself under the steaming shower. Someone else expertly flicked a customer’s rump with a wet towel, also while smoking. A Buddha-weight businessman sat in the tub, talking on the phone, cigarette in his other hand. I don’t generally smoke, even while swimming. Nor sing, even in the shower.

Men in bathhouses often break into musical without shame or concern. If there's a song on their mind, they do it. They just knock it out. I realise, now, that I could have bellowed a few power verses from something like Queen or Journey and no one would have said anything. But despite all the solo singing, acknowledgements between strangers were snorted – not spoken. I had previously considered this sort of greeting mostly the domain of pure pulp (“Malone grunted assent”) but quickly got the hang of non-syllabic speech. I added a pathic nod as I grunted across to one man with a sprawling black dragon ascending his left arm and most of his shoulder.

He then wouldn’t leave either of us alone. ‘Dragon’ caused my friend J particular anxiety with several vigorous handshakes, wagging his eyebrows for too long to be harmless. “What did that mean?” J asked after in a hush. “What does he want?”

“It’s probably nothing. Just something to do with, you know … sex,” I reassured him. “It’s fine, we’ll go through next door.”

Leaving the changing area, you troop right into the main hall and take it in: two giant, steaming baths, and more showers than you could ever need (five). Dragon leapt into one of the tubs, and beckoned us to join. We pointedly climbed into the other one. Snub over, a peaceful calm soon settled. A mantra began to repeat: this was a place to relax and forget the modern world, its deadlines and demands. Here, there was only the low murmur of voices in conversation, the playful splash of water – the occasional resounding ‘thwack’ from the massage tables. Jay and I exchanged contented nods. This was what we’d come for, a soak of old Beijing before it dried up like a dusty old crone.

Suddenly, the guy with a dragon on his back was on the move, clambering over the divide – the divide – and sinking into our bath. He kept his hands clasped nonchalantly behind his back, then began flicking water coquettishly on himself and at us. A coded signal? Local ritual? Haze the newcomers? He waded around, veered off, circled back, always smiling, nodding, splashing water, a pattern that continued until Jay finally broke the void and put it out there.

“Do you think he’s gay? I think he thinks we like him now.”

Dragon was yards away, oblivious to our commentary. Inches.

“Don’t make eye contact. Pretend he’s not there.”

“Eye contact?” Jay's scowl couldn't contain the impending mirth. “His dick’s about a foot from my face.”

That was true, irrefutably so. But it was a bathhouse – he had the right of way. I gave Dragon a terse smile dovetailing into a slight frown (the English way of telling someone to fuck off, I presume you know it?), and saw that his cheeks had turned a bright scarlet. Just then he reached over, tapped Jay warmly on the shoulder, and launched himself out of the water, like a humpback whale. He didn't land like one: his heel slipped on a puddle, somersaulting him onto his buttocks and back. You winced to watch it, but he was back on his feet within seconds, giving the room a reassuring smile, like a true professional, before limping off with the same agonised grimace. As soon as he hit the changing-room door, though, the whole act collapsed. Brimming with tears, his eyes lurched between pain, jangled embarrassment and, finally, the irreversible frustration of enduring a plain old fuck-up.

“Aww,” Jay conceded. “He’s drunk.”

Silently toasting Dragon’s departure, we opted for the sauna. According to a warning sign outside, drinking “while steaming” is not something the Chinese staff recommend – along with being pregnant, childish or enduring any heat found within for longer than about ten minutes. Cocooned in the back of the Finnish-style commode, flipping the bird at all of these, was Hong Sheng. He was 56, athletically built – a master at practicing limber yogic splits on tile-floored baths – and garrulous. He began gabbing the moment we sat down, introducing himself as a “TCM master” who had been practicing certain techniques, passed down through the Hong family since the Tang Dynasty, for over four decades.

A self-proclaimed qigong master, Hong was. Qigong is the ancient practice of duping superstitious fat cats into handing over large sums of cash by performing cheap magic tricks. “I can wear the shortest shorts in winter and be completely comfortable,” Hong cheerfully vouchsafed from his lotus position, streaming sweat as he ladled more water on the sizzling coals. “I can make water boil. I can make lights illuminate. Without electricity.” Prove it, you swine, I panted internally: Turn this heat down.

“Throughout history, people have perceived us as either gods or fools – or worse, madmen,” Hong lamented, presumably talking about qigong again. “Would you believe it if I told you I have actually spent some time in a mental hospital?” We would. If that wasn't the grimmest times of his life, it was up there – two months in a pitiless psychiatric ward run on medieval thinking, back in 2006. “I often thought about suicide,” he muttered, punctuating the remark with a rip-roaring fart while pouring still more water on the screeching rocks. Along with his spiel, Hong had the scars to prove it and invited us to peer at the marks on his muscular, twisted frame “from the operations I did on myself.”

The squat, silent fellow beside us had absorbed this whole conversation, all the while without stirring. But once our qigong master reluctantly left to his nude splits (performed on the wet divide of the baths), the stranger leaned over to make his own confession. “In Beijing dialect,” he warned, “that’s called bullshit.”

It was surely time to leave this hot, drunken idyll and venture into the bone-freezing reality of a night in deepest December. And there were those donkey dumplings we had seen advertised nearby to look forward to. While we donned our winter ensemble (leg warmers, vest, heavy-duty sweater, hat, boots, scarf, muffler, ski goggles), Hong stopped by to bid an extended farewell, list a few more qualifications and offer a possibly free consultation. Despite the frostbite lurking outside, Hong was wearing only a loose cotton t-shirt and plain khaki shorts. Conceivably it was the ineffable blessing of a soak in Shuangxingtang that had warmed his soul. Possibly he should have been back in the psych ward. Then again, perhaps he really was an ancient mystic imbued with temperature-warping psychic abilities. Or maybe he just lived in that hotel next door.

•

Robert Foyle Hunwick is a writer and editor in Beijing. He is working on a book about vice, crime and China's other attractions

Author’s note: Rumours suggest the expansion of nearby Nanyuan airport will shortly lead to the demolition of this historic bathhouse. Visit while you can

Original illustration by Marcus Pibworth for the Anthill. Photos from QQ news