The Road to Tibet

Climbing the highest plateau on earth – by Jeff J Brown

Leaving pullulating, steamy Chengdu and heading up to the Land of Snow is a great way to start the day. Up to over 3 km above sea level, up to the remoteness, isolation and naked beauty of the Tibetan plateau, where the air is pure and evanescent, and the sky as translucent as crystal. Up to an emptiness which defies the statistics that so many people live in China.

But you don’t just get on an escalator and saunter effortlessly to the Roof of the World. You have to fight your way up, and my samurai warrior today is an engaging and friendly man named Peng. His sword is a loosey-goosey steering wheel; his war saddle a well-worn driver’s seat; his stirrups an aged clutch, bad brakes and a sticky accelerator pedal; his reigns a cranky, grinding stick shift; and his mighty steed is a fully depreciated rust bucket of a bus that holds about twenty restless souls.

Today’s drive is empirical evidence as to why invading Tibet has happened only six times since its inception as a modern kingdom in the 7th century. It’s darn difficult to even get up here by bus, never mind armies on foot carrying supplies and weapons across deadly rivers and sheer valley walls. The gates of Jerusalem have changed hands over forty times in its long history and surely will again. But Tibet is the tallest plateau on Earth and a very inhospitable place for the uninitiated.

Each incursion is fascinating in its own right. The first assault was by 30,000 Mongol soldiers who wrested control of the kingdom in 1236 and managed to stay there until 1354, thanks to the efficient statecraft built by Genghis Khan (though he died in 1227). As in other areas the Khans conquered, religious freedom was assured and the locals were mostly left alone, as long as they paid their taxes and offered fealty to the Mongol state.

From 1717-20, the nomadic Zunghar people came down from the Turim Basin in what is now Xinjiang, and had fun terrorising and slaughtering the locals in Lhasa. The reason was good old fashioned sectarian violence – they didn’t like that brand of Tibetan Buddhism, so off with their heads! But these sword swingers only had control of Lhasa and the narrow surrounding valley of the Yarlung Tsangpo river. Tibet, however, is huge. The historical kingdom of Tibet is four million square kilometres, about the size of the Eastern United States or Western Europe. If you want to control a country this size, you have to be ready to put boots on the ground.

Tibet’s southern border is the Earth’s most Herculean Great Wall – the Himalayas. The Nepalese Gurkhas managed to come down from these mountains to briefly occupy one Tibetan city, Shigatse, in 1791. While they were lousy occupiers, they proved their martial prowess by sacking and destroying the regal and fortress-like Tashilhunpo monastery, one of the four great Gelugpa Buddhist temples on the plateau and then the seat of the Panchen Lamas. The Gurkhas had again proved Tibet was not militarily impregnable.

During the Sino-Sikh War, British Punjabis invaded in 1841, took a few towns, but didn’t last the winter. The Indian soldiers lost their fingers and toes to frostbite, were reduced to burning their gun stocks to stay warm, and slowly starved to death. So much for the genius of military logistics and planning ahead, not to mention gift-wrapped schadenfreude with a ribbon on top.

The Chinese Qing Dynasty managed to rule Amdo and Kham (modern day Qinghai and Western Sichuan, respectively) in fits and starts during the 18th to 19th centuries, but the main prize, what is now modern day Tibet, was pretty much left to its own devices. But all was not well in Tibet at the time, with political and religious infighting, unforgiving feudal overlords, pandemic illiteracy, serfdom, slavery, extreme poverty, and infrastructure and development straight out of the Middle Ages.

In 1904, the British under Colonel Francis Younghusband entered Lhasa, and forced a trade treaty. For the first time ever, the Qing Dynasty claimed sovereignty over Tibet and asked that the treaty go through them. Two treaties were signed, one Tibetan and one Chinese. Then in 1907, England and Russia solidified Chinese claims of sovereignty by signing a 1907 treaty with Beijing which recognised China’s suzerainty over the Land of Snow. That first shot across the bow of Tibet’s modern history and dreams of independence would come back to haunt them later.

Except for the medieval Mongols, none of these invaders controlled much of Tibet’s territory, just pockets of influence and a few cities. But Mao Zedong knew his history well, and the lessons from Tibet’s previous invasions were not lost on the Helmsman when he decided to gobble up Tibet. In October, 1950, one year after he stood atop Tiananmen Gate to establish the People’s Republic, the Tibetan Plateau was flooded with four divisions – 40,000 of the finest from the People’s Liberation Army, all battle hardened, revolutionarily inspired soldiers.

It took the 20th century contrivances of trains and automobiles to finally make for a geographic equaliser, and Mao swiftly took control of all four corners of the Tibetan kingdom, from the long and strategically critical southern border with India, Nepal and Bhutan, to anchoring Xinjiang with Tibet’s northern flank. Soon, he had unified all of historical Tibet, with Qinghai to the northeast and Sichuan to the east. The Tibetan leadership accepted the obvious, and signed away their freedom in 1951 with the ignominious Seventeen Point Agreement. Their medieval way of life was the perfect excuse for the Communists to look like benevolent, modernising saviors. And in many respects, they were.

***

All this is food for thought as our bus makes it out of Chengdu and heads towards to Tibetan plateau. The plains of the Sichuan basin are resplendent with corn, rice and tobacco fields, with quaint, neatly manicured villages and hamlets dotting the landscape, fading into the humid haze.

The national G5 highway southwest out of Chengdu is a modern four-lane affair. On this toll road we go through a 4km tunnel, several 2km ones and across tens of elevated bridges. The engineering is impressive. About 100km out of Chengdu, we suddenly turn off due west at Ya’an, onto a two lane road that rapidly narrows. This is the G318, as it sinews into a river-engorged valley towards Tibet. The section of the G318 from Tianquan to Luding along the Qingyi river is the first valley, and after Luding there are various interconnecting valleys and river tributaries that feed into each other, as we ascend to Kangding at the top of the plateau.

You don’t climb almost three klicks in eight hours without getting to marvel at the splendour of the Earth, its geography totally exposed. Between the Sichuan basin below and the Tibetan plateau above is a massive wall of the earth’s crust, nearly 3km high and 300km long. This is the fault line that caused so much devastation and misery during the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. It truly defies the scope of human scale that this gigantic cliff rise could move as much as it did, when that rumbler hit. The geological power of our planet humbles me, and I’m feeling Lilliputian as the landscape absorbs our tiny bus.

The Qingyi river is majestic. The water is running at a good clip, but is deep enough not to cause any cascades. It’s water from the glaciers of the Himalayas, working its way down to the Yangtze river below, then east until it empties into the waters of the Pacific. Agriculture starts at water’s edge with fruit trees, rice and vegetables of all kinds, terracing up the valley walls, with deciduous forests above, all the way up to the mountain tops. Villages, some quite big, hang onto the valley walls, occupying flattened areas just above the river shores. Every square centimeter of level land is producing something to eat.

We cross the river at Daduhe (Big Ferry River). This is where Emperor Kangxi built a bridge in 1706 linking Tibet to China. The Chinese still use, even today, this connection between the two territories as a historical argument for political unification. Outside Ya’an we pass a leprosy hospital, 5km away from the toll road. We also drive by a place called Sharengang (Murderer’s Ridge). What happened here and who was involved? I’m sure there’s a great local yarn that explains the fanciful name.

At a fork where the Qingyi is fed by a smaller river, we leave the main valley to follow this tributary, lurching onto a seriously bad road. The bus becomes a bucking bull rodeo ride. The sudden change in topography is dramatic, like entering a completely new biome. This deep, narrow valley has a Lost World feel to it – a cinematic leap in time to another era. Am I in the rain forests of Africa, on Avatar’s Pandora or in China? The walls are lush with tropical vegetation. Huge, thick jungle vines, towering bamboo forests with trunks as thick as your leg, banana trees and other plants and bushes I have never seen before blanket the ever more precipitous cliffs, as the river draws in its width and shallows out into a roaring, violent, churning mass of energy.

The local population lives in a series of hamlets ensconced in the lush vegetation. They laugh mockingly at Newton’s Law of Gravity, and seem as if glued with sticky-tack to the rugged cliff faces, suspended over the raging torrent below. I shudder to think what would happen if an earthquake ever struck this sublime, surreal valley. At least death would come quickly with that fall, bludgeoned against the numerous boulders that dot the river like a Greek mythology obstacle course.

The road is antediluvian, the traffic deadly and insane, but everyone else in the bus is nonchalant. I’m sure they have taken this route a hundred times before, to go into Chengdu for shopping, doctor’s appointments, administrative paperwork and the like. I’m taking it all, spoiled by the scenery as we cross back and forth over raging rivers. Halfway across bridges or at switchbacks, the views of the valleys are simply magnificent. Hanging 100 to 200 metres above the roiling waters below, as we cross each bridge or switchback we can look up and down the valley, and fully appreciate the scale and magnitude of the topography.

Why are there not more hydroelectric stations on these powerful rivers? Even further downstream, where the Qingyi river was wide and deep, I didn’t see any. China is the world’s largest producer of hydroelectric power, and 16% of that is from rivers. As of 2014 the country has 150 gigawatts of river power, with plans to expand this to 700GW. But apparently they prefer the grandiose kind, favouring the Three Gorges Dam and eschewing smaller units to serve locals. It may be a question of efficiency or scale of hydroelectric production, though later, in Guizhou, I see one river with a series of small hydroelectric plants.

Another shocker is the number of leisure cyclers who have been on this road since we started up the G318. We pass tens and tens of them, all Chinese, pedaling and pumping away towards the top. They are in it for the long haul, with plenty of gear in saddle bags, front and back. There are a good number of women and they all look to be in their twenties or thirties, traveling in small groups for a memorable summer vacation. They’ve got good mountain bikes, with three to four front gears and six to eight in the back, to tackle the severest of inclines – which they need on this road. They all wisely wear helmets, and most sport sunglasses and elastic biker face masks to help filter out the dust on narrow passages, giving them the look of roving bandits in training.

At lunchtime, we stop at an open air roadside restaurant in one of the cliff-hugging hamlets. It’s a communal collective of local cooks offering a selection of specially prepared dishes. One sells spicy, stewed potato peels. Others hawk cooked veggies of all kinds, luscious varieties of meat dishes, stews, noodles, tofu, and alien-looking mushrooms, with a huge wooden barrel of sticky Sichuan white rice available in unlimited quantity. There are drinks in plastic bottles, corn on the cob grilled on an open fire wok, and fresh-picked fruit for dessert, juicy, tree-ripe peaches, plums and pears. We are at 1,500 miles above sea level, the weather is idyllic and the sun is shining above but not directly on us. Below us is the roar of the raging river rushing ever downward. What more could you ask for?

For my tablemate, Mr Jiang, this utopian lunch setting needs a little extra kick. No sooner do we sit down than he pulls out a bottle of Chinese whisky from his coat pocket, cracks the seal, pours himself half a glass of late morning reveille, smiles and offers me one. I politely decline, we start chatting and he downs round one, then pours another stout glass and starts tucking in. I get a big bowl of the spicy potatoes along with a dish of stir fried sliced pork and spring onions in a white garlic sauce. I enjoy the juxtaposition: my blue collar meat and potatoes to Jiang’s liquid lunch.

Mr. Jiang is a local, and his thick Sichuan accent is off the charts, so beyond the twenty regular questions we struggle to communicate, although he understands my Mandarin inflected Chinese without problem. Speakers of foreign languages learn to do a lot of polite, earnest nodding, repeating the words they hear, sitting back and seeing what returns. Mr Jiang finishes rock gut round two before getting through his first dish, by which time round three is set and ready to go. This guy is good, and it’s only 11:30am. By the time we finish eating, he has polished dry the whole 375ml bottle. I suspect he will sleep through the rest of the trip, but I watch him and he never does. He does, however, make a beeline to the public toilets when we stop two hours later.

The last half of our climbing, winding ascent to the top gets quite hair raising at times. The G318 has no shoulder and long sections of it turn into muck and rubble. Rock slides are common, and can stop road traffic in its tracks, as we circumnavigate around the road repair works. What’s more, there is often just a scanty guard rail along the river side of this serpentine road. The sheer drop to the valley floor is so far in some places that we cannot even see the speeding river below us. Death would be swift should we slip or veer off this narrow strip of busted concrete. Not for the superstitious, nor the faint of heart.

Hats off to Prince Peng. He never drives faster than 30 to 35 kph, does an incredible job of negotiating the road’s twists and turns, keeps his cool and manages to get us safely up onto the plateau in one piece, arriving at Kangding after almost eight hours of driving. I shake his hand and thank him for his outstanding service, with heartfelt sincerity. And to think he’ll turn around and make the descent tomorrow, only to start the cycle over the day after tomorrow.

•

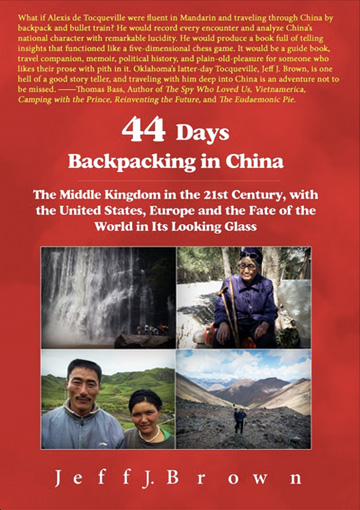

Jeff J Brown is author of 44 Days Backpacking in China, and blogs at Reflections in Sinoland. He grew up in Oklahoma, has lived in Brazil, Tunisia, Africa, the Middle East, China and Europe, and has travelled to over 85 countries. He currently lives in Beijing where he is an elementary school teacher in an international school

This is an edited extract from chapter 27 of 44 Days Backpacking in China. For more of Jeff’s adventures, buy the ebook at 44days.net, and print and ebook are also available on Amazon