Qi soup

A Chinese American rediscovers TCM in Beijing – by William Poy Lee

When she escaped China by marriage in 1949 and settled in San Francisco, my mother made eight promises to my grandmother. The seventh promise was to cook the traditional qi soups for her family to protect their mind-body balance and inner energy.

Along with every other American in the 1950s, my brother and I ate Campbell’s most popular soups – chicken noodle, cream of tomato, mushroom, split-pea. But at home, we also gulped down smelly, weird tasting Chinese soups – cow brain with ginseng, turtle, ox tail, four herbs chicken (from a live chicken, throat slit and defeathered in Chinatown).

As we ate, Mom explained the rationale to us in ways that made no sense at the time. It was to “adjust our inner fires” as we shifted from the warmth of summer into the chill of autumn, and then again as we entered the cold winter. Somehow this would inoculate us better than the flu shots we got at the public clinic. Or our bodies were too “hot” from eating Laura Scudder’s potato chips, beef chow mein and fried chicken, so we needed to bring down the inner fire or we would get sick.

This side-menu of folk soups was my rather foggy introduction to Daoist concepts and Traditional Chinese Medicine or TCM. Most of us know TCM as the needle – acupuncture – that mysteriously relieves pain, reinvigorates us from fatigue, or heals some chronic syndrome when western protocols are clueless. But herbal cures is another large part of it, and many popular TCM remedies involve boiling a mix of herbs down in a one-handle clay pot into a truly disgusting sludge.

My mother’s qi soups were never disgusting nor sludgy. They were quite tasty clear broth soups, a fusion of gourmet cooking and medicine. That, as I have come to grok, is the beauty of a culture where food is not just for daily nutrition or a mark of upscale culture (China has “foodies” too), but has evolved into a system of preventive and curative dishes, embedded into the four seasons, traditional Chinese philosophy and the patterns of healthy living.

In my interviews in the Toisanese dialect for The Eighth Promise, my mother detailed the ancient thirty day postpartum diet regime to rebuild a a mother’s depleted qi. On giving birth, Chinese medicine believes a mother has given up all her qi to the foetus, and a thousand years later, modern hospitals in Taiwan and major Chinese cities still offer thirty day maternity suites for the old protocols. Here’s what my mother told me about the qi soups:

“The first week soup cleans out the system of any leftover blood and membranes that did not come out during birth. We cooked this soup with hok mook ngee (black wood ear fungus), keem jeen (related to lonicera flower), nganh nah (ginger-root) and gai (chicken). The black wood ear fungus [mu er in Mandarin] grows on the bottom of tree trunks. It’s shaped like a human ear, is black in color, and has a very strong yin quality, enough to deplete the qi fire if we’re not careful.

“The second week soup ensures that the mother’s milk is plentiful, nutritious and sweet, so the baby will drink lots of it. This soup’s main ingredients included smooth bean curd, ginger, and a little bit of pork for taste.

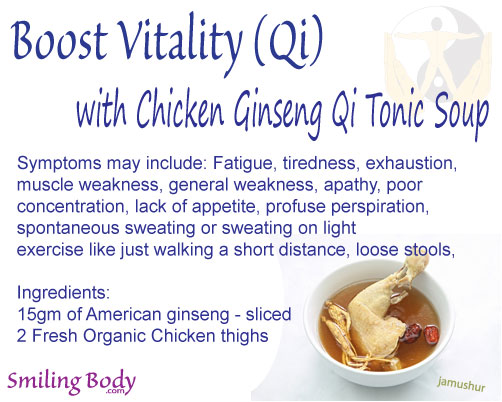

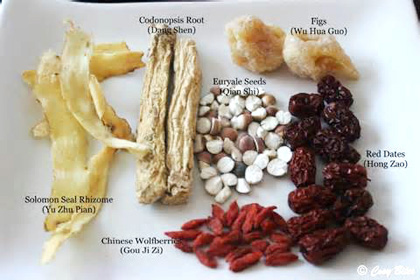

“We also served one main soup throughout the month, cooked with our five basic herbs: ginger-root, bok kee (astragalus) sliced to look like a doctor’s tongue depressor, hong on (codonopsis), which looks like a dusty brown twig, gee doc (red lycium berries), which are tiny, soft and wrinkled like raisins, and hung dow (red jujubes), marble-sized wrinkled berries with a pit inside. These five herbs gave the soup a sweet taste, built internal fire, and provided every nutrient a mother needed to rejuvenate, like a soupy multiple-vitamin.”

She also gave advice about what foods to avoid during this postpartum thirty days:

“No vegetables, because during this time vegetables easily cause diarrhoea. Why leak away the nutrients we spent so much time cooking! No fresh fish, because the scales weaken the qi body, causing the mother to get sick in the chest every winter. No beef, because it causes incontinence in old age. No duck because there are too many toxins in the meat. And no fruit because it flushes out all the special foods and will cause the same problem as beef when you’re older.”

“By the end of the month,” she said finally, “both the mother and the baby were strong enough to come out. This is the red-egg party time.”

***

After decades of suspicion about TCM, living in China again, it was in 2012 that I decided to go under the acupuncture needle. A friend in Beijing, Solomon, called me out of the blue and explained that a mysterious disease had completely depleted him of energy, that he had been on his back in bed 24/7. Not a single Western doctor could tell him what was wrong with him. But a Chinese friend had recommended a doctor at a public TCM clinic near Dongzhimen. Curious, I arranged to meet him there during a treatment.

I had my own agenda – my right hip had been hurting and stiffening over the past six months. Researching western medicine, it seemed all roads lead to artificial hip replacement, a painful, expensive process involving months of therapy afterwards to learn to live with a metal joint pinning my leg to my hip. It was a torment, with months of bed rest and physical therapy before normal use. Did I mention it’s usually not covered by insurance?

At the TCM clinic, a prone Solomon was literally a pin cushion, with needles all over his face and marching in two lines from sternum to belly button. As if that weren’t enough, the slender and lovely female doctor, Dr Jiao, attached some electrode clamps to several of the needles, then amped up the voltage until Solomon yelled “enough!” Later, he fully recovered.

Meanwhile, Dr Jiao listened to my symptoms and matter-of-factly encouraged me to come in, assuring me that acupuncture would heal the condition. That first treatment was like a miracle at Lourdes – the pain that had plagued me for months vanished temporarily. In my mind I was dancing, shouting “Hallelujah, Praise the Lord!” and throwing away an imaginary set of crutches. Three months of acupuncture treatment later, the pain progressively lessened and then disappeared. It’s been over two years now and has never come back.

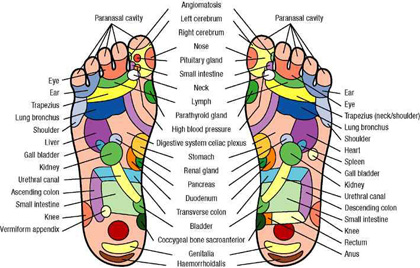

Later, for a bladder problem, I was prescribed a new diet regimen that required me to eat a lot of orange and yellow color foods, like yam, pumpkin, sweet potatoes, mangoes and papayas. Dr Jiao gave a Daoist TCM explanation for all this, relating to replenishing my “spleen earth energy.” Also, three times a week for an hour, I had to burn a very smoky and pungent cigar-size herb stick with the hot end aimed at my belly-button, the location of a major meridian point. A small boxy contraption held the herb stick over my navel.

Dr Jiao explained that TCM defines disease as the absence of qi in a given body part or area. TCM claims to move qi back into the bereft area through acupuncture, moxibustion (the burning heat nugget stuck to the top of a needle), cupping (like clamping a heated brandy snifter onto your skin), herbal medicine and diet changes. In other words, the same concepts of balancing and adjusting qi that my Mom was babbling to me about back in the day, while I rolled my eyes.

I started to study Daoist philosophy about qi flow, the basis for TCM. I started to understand that kidney or liver qi does relate to the kidney or liver alone, but is also a metaphorical way to understand qi networks within the body. I also learned a qigong set called the Eight Golden Treasures, taught by Dr Alex Tan, a Chinese-Australian who teaches and treats at The Hutong. The set is part of his class introducing the principles of Daoism and its holistic life-style. His emphasis is on preventive practices and awareness of how food impacts one’s health, with a list of season-appropriate foods.

From Dr Tan, I also learned that icy drinks with meals can make you sick in winter, as it dampens the qi fires in our stomachs, preventing the nutrients from getting to the different organs. As an home grown American, there is no way I will give up ice cold drinks. But Dr Tan, an Aussie who must also have his cold ones after a hard day’s work, said it’s only necessary to abstain from cold drinks two hours before and after a meal. I haven’t been sick with a cold or flu for three Beijing winters now.

So I’ve come full circle, from Mom’s Chinese medicinal soups in San Franciso to TCM treatments in Beijing. TCM has radically changed my way of understanding of the body, and now I can think in two healing modalities. Like the rest of modernising China, I have learned to navigate both knowledge streams, conscious of where the one may be more or less applicable than the other. I still enjoy Campbell’s soups, too.

•

William Poy Lee is author of The Eighth Promise, a Toisanese coming of age story in sixties America