In Search of Peach Blossom Spring

Arcadia with an entrance ticket – by Dean Barrett

The drive is not particularly picturesque, and some of the risks the driver takes seem almost suicidal, but no more so than the other drivers who barrel straight for us around dangerous curves. I lean forward to suggest to the driver’s wife that just possibly they might want to actually use their seatbelts. The suggestion is greeted with a smile of incomprehension.

I am reaching what could be the end of my journey in search of Peach Blossom Spring, China's mythical arcadian paradise, the ultimate unspoiled community, possibly the product of a poet’s imagination – or possibly real.

Peach Blossom Spring, known in Chinese as Taohua Yuanchi, is the best known work of the Chinese poet Tao Yuanming. It is a short description of a utopia which, despite its brevity, has had a tremendous impact on generations of Chinese poetry and fiction. Tao, one of China’s most beloved poets, lived at the turn of the fifth century AD, during the tumultuous six dynasties period. Known as the “Gentleman of the Five Bamboos”, the “prince of hermits”, and “poet of the garden and field,” Tao retired early from the life of an official and lived as a Taoist gentleman-farmer, working in his fields, writing poetry and drinking wine. His poems on nature have been compared to those of Robert Frost, and his style was later admired and even imitated by the greatest poets of the Tang and Song dynasties.

In Peach Blossom Spring, Tao describes how a fisherman sailing along an uncharted stream comes upon a radiantly beautiful peach orchard where “a myriad of scented petals floated gently downward, painting both sides of the river with their soft splendour.” Entranced by the orchard’s almost preternatural loveliness, the fisherman explores the orchard and, as he does so, notices an eerie radiance from within a narrow passage in a mountain cliff. He enters the passage and emerges into a land of beauty and mystery, a halcyon, idyllic agricultural community. In the fisherman’s China there is almost constant war and turbulence, and existence is at best precarious, yet here he is astounded to find “vast farmland and imposing farmhouses, fertile fields, beautiful lakes, mulberry trees and bamboo groves.”

The villagers are surprised by his arrival but pleased to converse with him. They tell him that their ancestors fled tyrants centuries before. They have been hidden from the world of sanguinary wars, internecine feuds and constant suffering, and know nothing of the outside world – nor do they wish to rejoin it. The fisherman is treated by the farmers as an honoured guest, and is feasted with all the fruits of their harvest and their finest wine. When the fisherman describes to them the violent and turbulent world he comes from, they shake their heads and sigh.

For several days the fisherman lives among them, spellbound by their good will and guileless ways. He watches in admiration as the people follow neither kings nor calendars, only the natural rhythm of nature. He senses a happiness and contentment in the villagers that does not exist in the China he knows. Excited as he is by his discovery, the fisherman eventually requests permission to leave Peach Blossom Spring. The villagers allow him to leave, asking only that he doesn’t spread word of their existence (“let your knowledge of us go no further”). This he agrees to.

But despite his promise, he carefully marks his route and reports what he saw to officials back home. The officials report this to the prefect of the district, who sends out an expedition in hope of finding the utopia. Yet to the fisherman’s amazement, his markings have mysteriously disappeared and the mission ends in failure. Try as he might, he can never find Peach Blossom Spring. Upon hearing of the fisherman’s discovery, a famed scholar plans another expedition but soon dies from a mysterious illness. No further attempts were ever made again to find Peach Blossom Spring. Until now.

In Peach Blossom Spring, the fisherman who chances upon the Arcadian community is from the small town of Wuling, which is now known as Changde and is in the southern province of Hunan. The poet himself lived near the beautiful Lu mountains, in what is now the neighbouring province of Jiangxi. In his retirement, Tao Yuanming was given to roaming the beautiful landscapes he loved, and his farm was not so far away that he could not have come upon the mysterious village nestled in the magnificent mountains which are now part of western Hunan province.

It is my theory (the reader might here wish to place the word “crackpot” before “theory”) that Tao Yuanming actually found Peach Blossom Spring and, as a poet, felt compelled to write about it. But to keep others (such as myself) from finding it and thereby changing it forever, he wrote his discovery as fiction, a tall tale of a remote, idyllic, isolated utopia so that none but the most unbalanced lunatic would actually believe it exists.

Well, I believe it exists.

The time passes quickly and at last I arrive. My goal has been achieved – after all this time, effort and expense, I am standing in front of Peach Blossom Spring. Or, at least, in front of several souvenir stands. I pay 50 yuan and enter beneath the ornate memorial arch. I pass a sign announcing a “pink flower forest”. The peach blossoms are past their bloom, and as I walk through the trees I pass very few tourists. Anyone with any sense visited the area during March and April.

Eventually I climb a series of steps and come across about two dozen men relaxing besides covered bamboo chairs with poles. The men are bearers and offer to carry me up the steep steps and around Peach Blossom Spring. At first I refuse; despite the enervating heat, being carried in a chair would make me feel like a 19th century colonial. But they are insistent and complain of not having customers, and I remember in Hong Kong when the last few active rickshaw-pullers sat by the Star Ferry with a sign nearby that read: “Don’t feel sorry for us; use us.”

And so I climb into a chair, and place my feet on the wooden rung. The bearers – one in front and one behind – lift the two long bamboo poles, and we’re off. When I see the steep incline of the steps set into the hills I wonder if I have made the right decision. Read all about it! Bamboo pole breaks sending tourist tumbling to his death at Peach Blossom Spring! Police say they are mystified as to why he didn’t come in March or April when the peach trees were in bloom.

But bamboo is incredibly tough, the men are surefooted and soon I am able to relax in the rhythmic sway of the chair. As we travel up and down the hills, I occasionally exit to enter temples or to climb the steps of pavilions. I catch glimpses of distant rivers, any of which could hide the real Peach Blossom Spring. But despite the beauty of the rolling hills, the area does not seem to be the ideal place to hide a community. Construction of temples here began in the 10th century, but it was only in the Qing Dynasty reign of the Guangxu emperor (1871-1908) that building was planned and carried out to approximate the poet’s story. The area is usually divided into four: Taoyuan mountain, Taoxian hill, Taoyuan hill, and the village of the ethnic minority known as Qin.

At one point I spot an opening in the side of a bosky hill and ask the bearers to stop. I walk up above to the narrow entrance and a roly-poly, irrepressibly jolly woman appears, offering to rent me a flashlight. She looks like a wannabe salesperson who has just that morning completed a home study course in renting stuff to foreigners. I take the flashlight and ask if there are any snakes inside the tunnel. “No,” she says. Then when I have paid her and am well into the tunnel, she says, “Yehsyu you yeh yen.” Night swallows, maybe. That rings a dull bell. It’s time to play the favourite Chinese game of using a pretty word to describe not-so-pretty-things. Night swallows are what some Chinese call bats.

But I’m determined to explore and, ignoring rustling sounds overhead, I begin my crouched walk through the tunnel. Eventually comes out to a clearing, where I expect I might find the real Peach Blossom Spring. What I find instead are my bearers already waiting for me at a tea house. They give me a look that says: Why didn't you ask, we could have told you where the shortcut is.

This is said to be the place where Tao Yuanming had his tea while enjoying the peach blossoms. That may be, but the tea is the worst I’ve ever tasted. I buy the bearers refreshments and ask them if there are mountains and valleys in China, especially in Hunan, where no one has ever gone. They say there are many places like that. I explain my mission and ask them what part of Hunan would they go to, if they wanted to hide a community from the outside world. They mention the mountains of Zhangjiajie.

Inside the first temple, someone asks me to write my “honourable name” in a book. I don’t like the sound of that because whenever someone wants me to write my “honourable name” in a book, it costs me money. It does here too. There will be more so-called temples where I will be asked to write down my “honourable name.” Looking at the names and considering the suggested donation, I assume places such as these have two sets of books, one for Chinese and one for foreigners. I learn from the woman working in one of these temples that there are no fewer than seven other places in China claiming to be the real Peach Blossom Spring.

At the ethnic village there are no villagers, let alone tourists. I seem to be one of the very few visiting Peach Blossom Spring off season in the height of summer. But some of the traditional farm implements are on display, including stone rice grinders which were once pulled by oxen or even by men walking in a circle. There are also chain water pumps sloping down into a lake, and the chair bearers happily untie them and demonstrate how they work. With the larger water wheels, men would place their arms over a horizontal rod of bamboo and use their feet to turn the wheels, which in turn moved water along a chute up onto the fields in need of irrigating.

Later, as we sit drinking still more tea in a hillside pavilion, I begin to appreciate the quiet beauty of this Peach Blossom Spring. It is not a spectacular, untamed beauty, boasting large swathes of cloud-shrouded craggy cliffs. Rather, it is a series of rolling hills and shallow valleys covered with copses of pine and cypress, clumps of magnificent bamboo and lush green banana plants, with an occasional splash of yellow-tiled roofs amid green trees, sloping gently down toward the Yuan river in the distance. But seeing Peach Blossom Spring without the peach blossoms is like seeing a woman d’une certain age without her makeup.

I think of the enormous influence Tao Yuanming had on Chinese literature. He has come to be regarded as China’s first great landscape poet, and a man loved for his character and behaviour as well as for his poetry. Unlike some of the highly embellished poetry which had been in favour and would be again, Tao’s prose and poetry avoided flowery words, false emotions and, for the most part, learned references. The scholar Liu Wuchi suggested that the Chinese love this poet above all others for “his warm personal insights and the spontaneous flashes of his candid heart.”

In the Tang Dynasty, Li Bai, Du Fu, Wang Wei, Han Yu and Bai Juyi all paid homage to the Gentleman of the Five Willows. In the Song Dynasty, Lu Yu, Wang Anshi and Su Dongpo did the same. References to him in other poems are often expressed in subtle ways: Li Qingchao of the late Song dynasty, regarded as China’s greatest woman poet, alluded to Tao in her poem in which she “drinks wine by the eastern fence.” There is even a scene in Shen Fu’s 18th century classic, Six Chapters of a Floating Life, in which his wife is stared at and interrogated by country folk prompting her to say that she feels “just like the fisherman who happened upon Peach Blossom Spring.”

I think of this sensitive and well educated poet from a Confucian family in decline, who struggled to make a living during a chaotic and unpredictable period of China’s long history. He attempted to serve officials near home as well as generals in such far away places as Chien-k’ang (present-day Nanjing), the capital of Jin. He then eventually resigned and returned home to eke out a living on his farm, finding solace and joy in wine and nature and friendship – and, of course, in poetry. But while he praised his beloved wine for its ability to “conquer melancholy, prolong life and exalt the spirit,” his five sons seem to have disappointed him. Not one of them, it appears, “goes in for the writing brush.”

Tao loved the chrysanthemums which grew by his eastern fence. Unlike so many flowers which bloom in spring, chrysanthemums are independent and hardy enough to bloom in the frost of autumn, and Chinese poets have often seen that flower (along with the pine) as a symbol of the unbending recluse, a man who spurns fame and glory to heed only the call of his cottage, his wine and his poetry.

The peach, meanwhile, has long been regarded by the Chinese as something very special, and Tao was no exception. This “fairy fruit” symbolises both marriage and springtime. In paintings one comes across the god of longevity holding the “peach of immortality”, or sometimes emerging from it. The head of the Eight Immortals is often portrayed holding the fruit. The fairy peaches found in the garden of the Royal Lady of the West offer immortality to those who eat them – but they ripen only once every three thousand years, so timing is crucial.

The brotherhood oath of the heroes of Romance of the Three Kingdoms was made in a peach orchard. Children were protected from evil spirits by the string of peach stones worn around their neck or by an amulet of peach wood. Both Taoist priests and practitioners of Chinese medicine place high value on the fruit, flowers, and bark of the peach. Problems with wandering spirits escaped from untended tombs? Just chop a branch from the east side of a peach tree, taper it into a wedge, and force the wedge into the door of the tomb. After this, no spirit will ever be able to leave the tomb again.

But my tranquil thoughts on peaches and poetry are interrupted by a small boy sitting on a rail below the pavilion playing a flute. As I watch him play it suddenly hits me. What better way to hide the real Peach Blossom Spring than by dressing it up and presenting it as a tourist attraction! Of course no one has ever found Peach Blossom Spring – because it has been hiding in plain sight. The residents have become ticket takers, souvenir hawkers, noodle vendors, chair bearers and tea house waitresses, a Houdini-like slight-of-hand so audacious it takes my breath away.

I dismiss the bearers and begin walking about on my own. People I passed previously smile at me as before, but now I’m onto their little game. If I’m right, and they’ve been trying to put one over on me, I’m going to bring truckloads of cameras, webcams and microphones up here and hook up Peach Blossom Spring on round-the-clock internet feeds.

After retracing my steps and looking for clues, though, the truth is I can’t be sure if this is the real Peach Blossom Spring camouflaged to look like a tourist attraction or simply a tourist attraction built to resemble the real Peach Blossom Spring. I get out my notebook and write: “Possible Peach Blossom Spring Location Number One: Peach Blossom Spring.”

I decide to check out the mountains of Zhangjiajie. If need be, I can always come back here to continue my investigation. A relaxing train ride will help me reflect on my new theory. Besides, if these people have been pulling a fast one all these years, after they are exposed it won’t take much to turn this place into just one more gated suburban community.

•

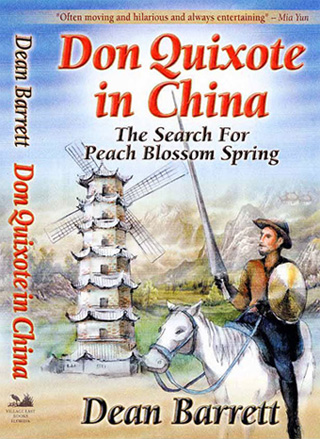

Dean Barrett is a writer who currently lives in Bangkok. He has been in Asia for over three decades, including 17 years in Hong Kong as managing director of Hong Kong Publishing Company. He has written several books on China and Thailand, and an award-winning play, Bones of the Chinamen. This is an edited extract from his book Don Quixote in China: The Search for Peach Blossom Spring