Northern Lights

A plunge into sub-zero at China's northerly tip – by Branson Quenzer

In northern China the cold can make a man stir crazy. Winter dreams visit you in minus forty-degree celsius temperatures. The aurora borealis, nature’s own 70s psychedelic montage, is said to make appearances in Heilongjiang province’s northernmost village of Beijitun. Modern technology now tracks the northern lights, and on a good night the aurora fairies might just dance. Away from the ice lights of Harbin, we were off to find the earth’s own nightlight.

I was joined by a friend from down under – removing himself far from the summer beaches of Bayern Bay – along with his girlfriend, a Heilongjiang local. The train to Mohe, the end of the line and launching point for the far north, was not an eight hour trip but 18 hours, made easier with big green bottles of Harbin’s finest Hapi beer. We met a pair of travelers from southern China on the train, and in Mohe the five of us piled in a microvan heading to the ‘northern lights village’.

The drive took two hours, on dark mountain passes in temperatures low enough that the glass froze. Multiple panes were stacked then taped on top of one another in front of the driver, like he was peering out of an igloo on wheels. The southerners had made reservations at a village homestay, otherwise we would have been out in the cold. At Beijitun, there were no northern light in sight, just a sign warning not to walk across the river. The Heilongjiang or ‘black dragon river’, also called the Amur, is the border between China and Russia, where my Aussie friend and I hoped to sneak across for a look.

The next morning, reconnaissance began as the Chinese three of our tourist troop marched with PLA soldiers to territory forbidden for foreigners: the army outpost guarding the border, mostly against the occasional inebriated Russian who stumbles a little too far south. We strolled along the frozen river, peering across to the Russian banks on the other side, making a stop at a hole drilled into the metre-thick ice, where some locals were fishing. All the while we scouted the watchtowers on either side of the river, looking for any blind spots which could help a possible night crossing.

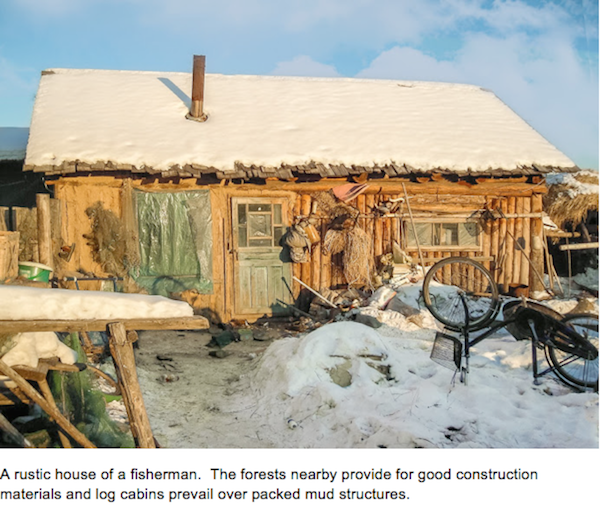

The fishermen said that the Russians cross the border from time to time, to steal fishing nets. To give them back the Russians barter for cheap homebrew baijiu, hurled by the Chinese over the no-man’s zone. The border is marked by wooden stakes and tattered flags, frozen midstream every 50 metres, demarcating Russia from China. We asked the fishermen if they had ever dared to set a foot on the other side of the river. They hadn’t, even after 30 years of fishing ten metres away from Russia.

Leaving our furry-hatted comrades, we made our way back to the village, where we were stopped by a small PLA platoon demanding in Russian to see our passports. I had my American passport with me, but my Australian friend had left his back in Harbin, so had no proof of legal residence in China. I spoke to them in English, and my grin didn’t set their minds at ease. The ranking officer talked in Chinese with his troops, as I tried to steer the conversation away from passports and towards us being “not Russian”. It fell on deaf ears, and they said they would take us in for questioning.

But as they turned and we started to follow, the officer got a call and changed his mind. Seemingly convinced we weren’t Russians illegally crossing over, he warned us to be careful: don’t go past the posted signs in the middle of the river. After they left, we laughed off our crazy idea of crossing the river.

Soon after, a car pulled up and our Chinese compatriots were dropped off by the local public security bureau. The Australian’s girlfriend jumped into his arms, worried, then quickly retracted her embrace with a gnarled “be careful”. While they were up in the guard tower in the PLA outpost, they heard radio calls about Russian intruders. As the armed soldiers approached us, ready to detain us for questioning, she had snatched a pair of binoculars and shouted at her guide for them to let us go.

The night came but the northern lights did not. We asked what time of year the northern lights usually dazzle, pointing to the postcard pictures with bent corners and faded colors hanging in the general stores all over town. The answer was always, “You can see them here, but not now.” Some said in spring, others in fall, but for sure the answer was not now. After our encounter with the armed forces and rescue by our friends, we were going nowhere under the cover of darkness.

The third night threw nothing but black at us. My beard was frozen, and there were icicles everywhere. At the general store, the only liquid that could survive outdoor temperatures of minus forty degrees was baijiu. A slug chased by a beer slushy and a drag of some local tobacco helped pass the time and fight the cold.

Drinking with the Australian, as the bite of baijiu faded, so too did our fear of crossing the frozen river. The last slug from the bottle was the last bit of liquid courage or stupidity that either of us needed.

A few preparations were needed: camera flash off, gloves on, and two pre-rolled cigarettes. We staggered to the end of the village, then to the riverbank where we felt confident we wouldn’t be spotted. Stop and go, stop and go, through the waist-deep snow, with no aurora borealis to give us away.

In Russia, we took a photo, then laid down on our backs to smoke. The only lights that night were the two faintly glowing tips of our cigarettes. We left the northern bank of the Amur behind, and snuck back to our beds in Beijitun for a deep night’s sleep, dreaming of our own northern lights.

•

Branson Quenzer is a photographer and artist, originally from New Mexico

A different version of this piece originally appeared in a Harbin city magazine. Photos and captions by the author