In the Gulou days

Reminiscence, history and a walking tour of Beijing – by Alec Ash

Nostalgia is hard to keep up with in China. That old bar, that old neighbourhood, that old friend – memories accrue quickly along with the fast turn-over here, silt at the bottom of a swift river. Circumstances change, people come and go. Just count the number of new restaurants on your street. The way we talk about last year is the way folk back home talk about last decade. The constants – rent hikes, food poisoning, strangers taking selfies with you – are almost comforting.

The space I feel most nostalgic about in Beijing is the courtyard between the drum and bell tower. I first saw it in the summer of 2007, a fresh graduate on my first trip to China. I was meeting my brother’s schoolmate Max Duncan (a videojournalist still in Beijing), the only person I knew in town, and the taxi dropped me off right in the middle of honking traffic at the south side of the drum tower. But just around the other side was a rectangle of quiet, green fringed with stone slabs and grannies dancing to a boombox. Max was squatting to one side with a cigarette, nattering away with a grandad in Chinese. The next summer, I came back to learn Chinese and stayed.

Six and a half years later, that courtyard is there and it’s not. Everyone in Beijing will have seen the demolition works, the square cordoned off as the houses and bars around it were torn down (some great pics from Matthew Niederhauser here). There had been loose talk about it for years, with initial plans for an underground carpark scuppered, before in 2011 the relevant organs announced they would "try our best to preserve the appearance of the ancient capital." In the end, the property developers always win, but at least it didn’t go the way of Qianmen with its faux Qing boulevard. The refurbished courtyard, spangly lamposts and all, is still just an empty square.

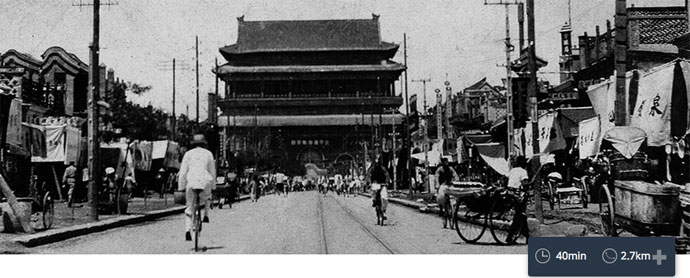

It’s not the only transformation the area has undergone, of course. That’s the solipsism of nostalgia – you think that the earliest version of a thing is when you first came along. To those who were here in the 80s, or all their life, talk fondly of the courtyard in 2007 and they will only roll their eyes. Just look at this picture from Life magazine, undated but I’m guessing from the 70s. Changes are as part of Beijing’s fabric as constants, and it’s a fool who thinks yesterday was more authentic than today. Still, in a city with an overdeveloped sense of the present, it helps to remember that every empty square overflows with history.

The drum tower used to be the geometric centre of town. Most of what we think of as old Beijing – the Forbidden City, the city walls – was built in the 1400s in the early Ming dynasty. But when the Mongols invaded from the north and established the Yuan dynasty in 1271, Kublai Khan took the settlement of Yanjing for his capital and called it Khanbaliq, "city of the Khan" – or in Chinese Dadu, "big capital.” Back then the city had square earthen walls (you can still see the ruins at Beitucheng) and had recently been ravaged by fire.

The oldest parts still standing today date back to what the Mongols built, including the hutongs – a Mongolian word – and the drum tower, erected in 1272 at its heart.

In 1402, when the middle of the Middle Kingdom had already moved to the emperor’s throne room, the drum tower was rebuilt by the Yong Le Emperor, and then again in 1747 by the Qianlong Emperor, the version still standing (refurbished) now. It’s 99 feet high, so as to avoid blocking spirits who were said to cruise at 100 feet. The watch was sounded every two hours, 108 beats of the drum each time, to coordinate offical activities in the days before digital watches. And when that drum was beaten, you could hear it all the way out at the furthest edge of town.

The bell tower to the north of the square – built in 1272 along with her brother – was also redone in stone by the Qianlong Emperor in 1745 (see picture above) after a fire destroyed the original. The bell, a brass and gold alloy, weighs a whopping 23,000 pounds and tolled every day until as recently as 1924. There’s also a rather gruesome legend of how the bell maker finally got the alloy to cast, replacing the duller iron bell, at the price of his daughter’s life. (You can read that along with more info here.)

Inspired by history reading, the warmer weather and my own incurable nostalgia, I’ve teamed up with the city walking app VoiceMap to record a forty minute, 3km walking tour from the drum tower through the hutongs to Yonghegong lama temple. It’s a fun route, and takes you past pigeon aviaries, mahjong parlours and an ancient liquor museum, as well as stops at the imperial college and Confucius temple. The route might be old hat to China hands, but it’s designed for visitors.

You can download the app and buy the tour here for $2.99. There’s also another Beijing walk by Paul French, a guided tour of locations in the 1930s Beijing badlands from his book Midnight in Peking. I guess that’s what this post has been leading up to, in its own hutong like winding way. But that’s how nostalgia works too, taking you the long way around to where you could have begun.

I’ll leave you with a quote from The Search for a Vanishing Beijing by MA Aldrich, a book I’ve been enjoying recently. It’s a series of walks around old Beijing, trying to recapture that sense of history. “With effort,” Aldrich writes, “and admittedly perhaps a touch of romantic eccentricity, I found that, for a moment or two, I could force the concrete apartment blocks to yield to Old Peking. Sometimes it felt as if a ghost stepped out from behind the smog and concrete and approached me, eager to bring back to human memory forgotten people and stories. He seemed to be delighted to find an audience, although a suspect one on account of the bridge of my nose.”

Happy rambling.

•

Alec Ash is a writer and journalist in Beijing, and editor of the Anthill

NB: Because GPS is fucked up in China, when you download the VoiceMap app and Beijing walking tour for the first time, disable your Wifi and data connection (in settings>mobile) before you hit the "start" button. That way you'll see the offline map, which should display correctly, as opposed to the online map, which displays wonky and guides you straight through Houhai lake