Foreign elements

The unbearable lightness of being an expat in China – a Q&A with Tom Carter

Over at the LA Review of Books China blog, I interview Tom Carter in the wake of the collection of true stories from expat China he edited, called Unsavory Elements. Tom is originally from San Francisco and has been living in China for a decade. He also did a book of photography based on trekking 35,000 miles through 33 provinces for two years. I asked him about expat identity issues, to try and get under the skin of those “masochistic” enough, in his words, to call China home.

•

Why did you feel there was a need for a collection of stories and anecdotes by Westerners living in China? What is it about that experience that interests you?

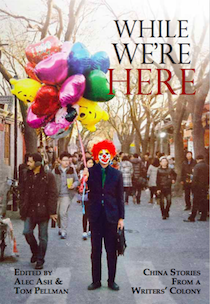

It was a project whose time had come. The past decade has seen an unprecedented number of new books and novels about China, but aside from a handful of mass-market memoirs there was nothing definitive about its expatriate culture. As an editor and avid reader, I had this grand vision of an epic collection of true short stories from a variety of voices that takes the reader on a long, turbulent arc through the entire lifetime of an expat – bursting with ephemera and memories from abroad. That’s how Unsavory Elements was conceived.

Of course, the landscape of China in 2013 is vastly different than 2008 – generally considered the new golden age for laowai (foreigners) – and virtually unrecognizable from 2004, which is when I first arrived. Such rapid changes are the subject of just about every book on China these days. But swapping stories with other backpackers I bumped into on the road while photographing my first book, I noticed that there was something profound about our experiences and adventures – the tales we told might just as well have occurred in the 1960s or even the 1860s. And that’s when it struck me: the more China changes the more it stays the same. So I wanted to switch up the trends of this genre and feature stories that were not only timely but timeless.

But how has the foreigner community in China changed over the past decades? Do you feel there's anything Westerners in China have in common, among all the diverse reasons that people have to end up here?

Expatriates in China are certainly a motley crew. I’ve lived and traveled extensively across many countries in the world, but none seem to have attracted such a diverse crowd as China, this eclectic mix of businessmen and backpackers, expense-account expats and economic refugees. It really could be the 1800s all over again, like some scene out of James Clavell’s novel Tai-Pan [about the aftermath of the Opium War] except now with neon lights and designer clothes. What we’ve seen this past decade surrounding the Beijing Olympics is history repeating itself. The Western businessmen who have come and gone these past ten years during the rise of China’s economy are the exact same class of capitalists who populated Shanghai and Hong Kong in the 1800s. They’ve come to make their fortunes and then get out – which is what we are witnessing with the recent expat exodus [now that China’s economy shows signs of faltering].

The darker side of China’s history also seems to be repeating itself. The Communist-conducted purges of “foreign devils” and foreign-owned enterprises that occurred in the Cultural Revolution are happening all over again – perhaps not as violently (with the exception of the looting of Japanese businesses during the Diaoyu Islands dispute in 2012) but certainly with as much vitriol. There was last year’s poster depicting a fist smashing down on the characters for “foreigner”and various video footage (possibly staged) of foreigners behaving badly, used to justify their Strike Hard crackdowns [against foreigners in China with black market visas]. The title Unsavory Elements is a playful homage to Communist terminology. To be sure, China has a love-hate relationship with outsiders – our success and our status here rises and falls on the whims of the government. In spite of this, as many foreigners continue to arrive in China as leave (or are expelled). So what do we all have in common? If nothing else, a degree of masochism.

And how, if at all, does living in China long-term change you?

I expect it’s tempered me, much like in metallurgy, from the constant pounding and heating and cooling and reheating of my patience. Suan tian ku la (sour sweet bitter spicy) is an old Chinese adage, and this country definitely serves up its share. But it hasn’t been easy to swallow. Westerners tend to arrive in China a bit hot-headed, and we’ve all had our explosive moments: with the taxi driver who runs his meter fast or takes us the long way, at a train ticket office jostling with queue jumpers, due to endless red tape, or when you are ripped off by your business partners.

Few foreign writers ever admit to having these moments so I encouraged my anthology contributors to be more forthcoming about their darker feelings – seeing red, so to speak. Alan Paul, writing in the book about a stressful family road trip across Sichuan, has a line: “I stood there bitterly looking down into that hole, silently damning New China’s incessant construction.” I can relate to that every time I hear a jackhammer. Even the famously mild-mannered Peter Hessler confesses in his essay to going ballistic with his fists on a thief he catches in his hotel room. I’ve been there as well, taking out all my pent-up frustrations on some poor pickpocket who wasn’t quick enough to escape the reach of this 6’4” foreign devil. I expect that having had my patience tried so often here has forged me into a calmer, more levelheaded person than the clenched-fisted, teeth-gnashing, Thundarr the Barbarian in Beijing I arrived as.

A foreigner also has special status and perks from being in China – for instance, they always stand out, whereas back home they're just another face in the crowd.

Special status, yes, but not in the way it’s been mythologized. Sure, in the countryside it’s nice to be invited in for tea by villagers who’ve never encountered a Westerner before, but in Shanghai you’re bumped into and cut in front of and run over by cars like any other laobaixing or common person. That oft-eulogized “rock star status” was more of a vague concept that the Chinese used to have about the West – the branded clothing, the rebellious music, the casual sex. But actually there’s nothing special about being gawked at, openly talked about and cheated because it’s assumed that you’re wealthy. And there’s certainly nothing special about the hell-like bureaucracy foreigners are burdened with, or not having access to basic public services like hospitals, schools and even hotels, or the frequent suspicions that the government casts over us.

In fact, in just the past five years following the global recession of 2008 – during which nearly every world economy collapsed except for China’s – our collective esteem in the eyes of the Chinese has plummeted from superstar status to that of some invasive species, a metaphor which the environment journalist Jonathan Watts also makes in the book, comparing non-indigenous plants with foreigners. And there’s a wholesale fumigation of Western corporations [that exploit China’s low labor costs], which the Communist government now considers a threat, like the imperialist military incursions of centuries past. They want and need our business, but they are no longer going to make it easy for us. As a result, the Xi Jinping administration is coming down hard on foreign firms that have historically gotten away with shady practices like price fixing, influence buying and general non-compliance.

Do you think it's hard to adjust to life back home if you return? With no cheap taxis, eating out, cleaners, massages...

I honestly couldn’t tell you. I’ve only been back to the States once in nearly a decade; China is “home” now. I’m not that laowai who skips out on China when it’s convenient, or because living here is no longer convenient. I’m also not that Westerner who has a driver or only takes taxis – I ride public transportation and my rusty trusty 40-year-old 40-kilogram Flying Pigeon bike. Nor do I hire old ayis [housekeepers] to do my dirty work – my wife and I raise our child ourselves, make our own meals, and clean our home ourselves. I can just hear all the gasps from colonialist-minded “enclave expats” who could never conceive a life in Asia without servants.

I did live in Japan for a year after four straight years in China, and found the orderliness and politeness and emotionlessness of it all quite difficult to adjust to. So I spent the following year wandering around India, which provided me with a much-needed dose of dust and disorder. After that I returned to China and for the following few years lived in my wife’s native farming village in rural Jiangsu province. That to me was like an epiphany, as if I had finally found home. But for my wife – who in her youth had strived to escape the countryside and eventually made her way up to Beijing, where we met – it was coming full circle back to where she started. So now we divide our time between Jiangsu and Shanghai, which I guess gives each of us the best of both worlds.

I’ve had friends who went back home after living in China, but missed the excitement and buzz so much they couldn’t help but come back. Is China a drug?

I should first disclaim that the Ministry of Public Security takes drug dealing in China very seriously, as Dominic Stevenson, who wrote about his two-year incarceration in a Chinese prison for dealing hash, can attest. But I’d venture to say that, like any drug, it depends entirely on the user’s own state of mind. If we’re making metaphors, for old China hands I’d imagine their time here draws parallels with the soaring euphoria and bleak depths of smoking opium, while China for the uninitiated is probably a bit like bath salts: the constantly convulsing nervous system, the paranoia, the god-complex, the rage.

I’d liken my own China experience to a decade-long acid trip. It began with liberating my mind from the restraints of Western society. Then I departed on an odyssey that took me tens of thousands of miles across China, experiencing various metaphysical and spiritual states as my journey progressed, punctuated by periods of intense creativity due to my heightened sensory perceptions. To a background score of warped erhu and guzheng [classical Chinese instruments], and the looped calls of sidewalk vendors echoing into the void, the kaleidoscopic chaos of this culture surged around me like the Yangtze river – in outer space. Now I’m one with China’s cosmic consciousness. I want to reeducate the communists with love. Or maybe I’m not even here. Maybe I really did perish during my Kora around Mount Kailash and none of this ever happened ...

Your own story in the book is about a visit to a brothel with two lecherous laowai. How representative do you feel that this kind of foreigner in China is, especially those who come to try and pick up Chinese girls?

It’s been fascinating for me to see how much polemic this single story has stirred. I kind of knew I’d be martyring myself when I decided to include my account of a boy’s night out at a brothel in the anthology instead of, say, a story about my marriage in a rural village, or about delivering our firstborn son at a public People’s hospital in the countryside. My publisher, Graham Earnshaw, even tried to warn me about the inevitable ire that would follow and suggested I pull the piece for my own well-being. His forecast was unfortunately accurate. Immediately following a Time Out review that dedicated most of its page space to criticizing my brothel story, certain women’s reading groups called for my arrest and deportation from China because, they said, I “patronized teenaged prostitutes”.

And yet, the story has received as much praise as it has hate. An equal number of readers seem to find it refreshing that a foreigner is finally writing about experiences many single males in the Orient have had but never dared admit – especially not in print. And considering the Party’s penchant for keeping extensive dossiers on Chinese and foreigners alike, I can understand their reticence. But I can’t help but consider as downright disingenuous the glaring omissions of any situation involving prostitution – an impossible-to-overlook trade found in nearly every neighborhood in every city and town – by certain best-selling Western authors in China. Do they not consider the women of this profession worthy of writing about? Or are they simply lying?

I’m not saying I had some altruistic intention with my story – it was just an absurd situation that my friends and I got ourselves into that also happened to make for ribald writing. But the truth is, I conceptualized the entire anthology around that brothel incident, because I wanted to compile a collection of candid and truthful experiences that left nothing out, including visits to your neighborhood pink-lit hair salon. Only the discerning reader can tell you how representative it is of them, but maybe, nay, hopefully, my story will kick off a new era of honesty by Western writers in China. We’ll see.

•