In the Autumn Cold

A party in the guardhouse – by Cobus Block

Yafeng was standing at his post beside the guardhouse, rocking back on his heels and looking into the sky when I walked through the gate. A gray, padded overcoat bloomed out over his slender frame like a worn traffic cone. Topped off with a battered officer’s hat, he looked more comical than intimidating. As the most sociable guard in our apartment complex, he had a habit of talking with residents whenever he saw an opportunity. It was not long before we became friends.

“How are you?” I greeted him.

“Good. I’m leaving tomorrow,” he replied with a smile.

“You’re leaving?”

He nodded. “Going home.”

“For vacation?”

“No, just going home.”

“Really? For good? Did you get a job?”

He waved off the question and looked across the street. “A job ... that’s ... how do I explain it ...”

“So you don’t know yet.”

He laughed. “Not really. What are you doing tonight? If you’re not busy I’d like to invite you to dinner.”

“What time?”

“Can you wait ten minutes? The guys just went to get some food and drinks. We can wait in the guardhouse.” He opened the door.

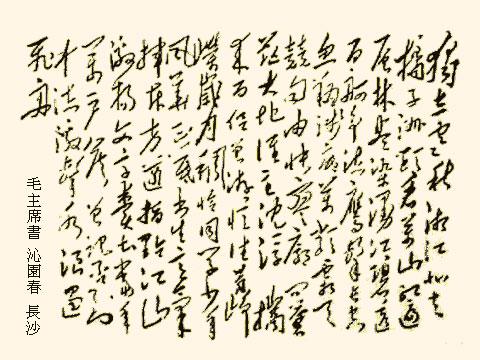

The guardhouse was a square cement room large enough for a dilapidated office chair, a plain desk and a two-plank bench, which, when covered with a cotton comforter, became a bed. Newspapers, stained by the smoke of countless cigarettes, not-quite covered the four walls. Scribbled drawings, women’s names and phone numbers were etched into the yellow paper. One small, square set of characters caught my attention.

“What’s this?” I asked.

“What? Oh, that’s a poem.”

The characters were written in crooked cursive with long, dangling ends.

“I can’t read any of it, what does it say?” I asked again.

Yafeng came closer and squinted, “It’s calligraphy. I can’t read any of it either,” he said with a shrug. “I think it’s a poem by Chairman Mao.”

The door opened. Two guards entered carrying styrofoam take-away boxes and bottles of beer. One was Liupeng. The other I did not recognise. They set down their cargo and turned towards us.

“You’re here, huh?” Liupeng greeted me with a smile.

The guard I didn’t know introduced himself as Guxi. I asked if he recognised the poem on the wall.

“It’s a poem by Chairman Mao,” he said as he moved closer and began to read. “Alone ... I ... – I can’t read it all,” he finally admitted.

Liupeng set his beer down and joined us.

“Alone I stand in the autumn cold,” he read solemnly, sounding out each syllable with rhythm and conviction, “Past Cheng Island the Xiang northward flows. – It’s Changsha. Don’t tell me you don’t recognise it!”

“I know it. I just couldn’t read the bad handwriting,” Guxi said.

Yafeng moved the registration desk to the middle of the room and placed the opened the styrofoam boxes on top. Each brimmed over with chunks of potatoes, peppers and chicken covered in thick sauce. Yafeng and I sat on the bench against the wall, while Guxi sat opposite us on the lopsided office chair. Liupeng squatted at the end of the table and lifted his bottle of beer. “Ganbei!” Then he hesitated. “How do I say that in English?”

“Cheers!” Guxi said.

“Cheers!” we all repeated.

We had no rice and no individual bowls, so we leaned over the trays together and slurped at the contents. Yafeng had paid for the meal, so, as is customary in China, he began complaining – the portion was too small, the flavour was not strong enough, there was not enough chicken. He shook his head and sighed – it was certainly not as good as the dishes in his native Baoding.

“Do you eat this kind of food over there?” Liupeng asked, referring to my hometown.

“Not really,” I replied.

“There really are too many differences between China and foreign countries,” Yafeng said. “Especially in politics. In America, they have a whole bunch of political parties and they are all constantly fighting with each other.” He looked to me for confirmation.

Several days earlier, Yafeng and I had a conversation that touched on politics. After several attempts to explain the American system, I realised he was only becoming more confused. This time I nodded my head in agreement.

“But here in China,” Yafeng continued with some patriotism, “We only have one party!”

“What are you talking about? There is more than one party in China!” Liupeng cut in. “There is the Democratic League, the Association for Promoting Democracy, and so on.”

“Ok, Ok, but they all ‘follow the lead of the Communist Party’.” Yafeng quoted the official (and entirely accurate) status of China’s rather irrelevant additional parties.

“Don’t forget the Nationalists,” Guxi said in reference to the exiled KMT, which has ruled in Taiwan since Mao threw them off the mainland in 1949.

That made the other two laugh. They took turns cracking jokes at the expense of the Taiwanese.

Liupeng called for a toast, “To the liberation of Taiwan!”

We drank to “liberation”.

Conversation shifted from politics to movies to girls and finally settled on cars. Everyone named his dream car and what he hoped to do with it.

After a short argument over whose car was best, Guxi stated the obvious. “Anyway, it doesn’t matter. None of us is ever going to have a car like that.”

“I will,” Yafeng said with exaggerated confidence,.“I’m going to get to that upper class and have it all – a mansion, a celebrity girlfriend, a nice car ...”

Liupeng looked across the table at me. “You know, there are three classes in China – the rich, the poor and the destitute. Us? We sit at the very, very bottom!”

“Then I guess there’s nothing for it but to drink!” Yafeng said as threw back his head and gulped from the bottle.

A muffled voice from outside hooted, “By Heaven, they’re drinking beer!”

Yafeng choked, coughed and dropped the foaming bottle from his lips. The door yanked open and in swung a burly man in black leather. His face was large and cracked – its proportions exaggerated by a small ball cap, which perched precariously on top of his closely cropped hair.

“What’s this! You’re drinking on the job?” he bellowed. Yafeng stood with the bottle hid behind him and a stream of beer trickling off his chin.

“Hello Uncle,” he said awkwardly. “It’s like this ... you see ... well, I’m leaving tomorrow, so ... so we’re having dinner together ...”

“You’re leaving? Huh! Well, that’s too bad,” the burly man said in a kinder tone, “How about the rest of you –”

He saw me and stopped mid-sentence.

“Hello,” I said in the polite form.

Hel-lo!” He pronounced loudly, splitting the syllables. He nudged Liupeng and pointed to me, “This guy speaks our Chinese?”

Liupeng said I could, and I repeated his answer to prove it.

“Well I’ll be damned! He can!” he smiled a big, toothy grin. “Say, what do you think of Chinese food, do you like it?”

“I like it very much,” I responded.

He bobbed his head in satisfaction then looked at the other three, “Alright. I’m going.”

He pushed the door open and gave a comic salute. “Have a good trip, you!”

“Thank you, Uncle!” Yafeng responded.

“Who was that?” Guxi asked as soon as the door closed.

“It’s the cleaning lady’s husband. He lives here,” Yafeng replied and reached for another potato.

We ate faster now. The food was cooling and we had no time for conversation.

“Someone else is coming,” I said, nodding at a uniformed figure approaching the door.

Everyone raised his head to look.

Yafeng spat out an expletive, “It’s Mr. Zhang. What do we do?”

Liupeng shook his head and motioned for everyone to keep silent. There was a shove at the door and a curse followed by several progressively louder bangs. Each blow reverberated in the tiny room and rattled in our ears.

“Pull!” Liupeng yelled at the stubborn intruder, then muttered something under his breath.

The door screeched back over the concrete. A tall man stomped in, his face red from annoyance and liquor. Everyone greeted him respectfully. He leaned against the wall and looked around the room with a scowl.

Yafeng leaned over to me and cleared his throat, “You have somewhere you need to be, right?”

I nodded my head.

“You ... you can go now,” he said with a grimace.

I understood his meaning, said goodbye to Liupeng and Guxi and stepped out the door. Yafeng accompanied me.

“I’m sorry,” he started to apologise. “This guy ... this ... well, private affairs should only concern those who –”

“Don’t worry,” I told him, “I got the idea.”

“I am really sorry –”

“No problem,” I repeated. “I hope you have a safe trip.”

Yafeng thanked me and held out a cigarette. “And I hope you enjoy the rest of your time in China.”

I took the cigarette and shook his hand.

I did not meet Yafeng again. He left me no contact information, and his friends Liupeng and Guxi both disappeared soon after. Still, Liupeng’s solemn tone rings in my head as I recall the words of Chairman Mao. Alone I stand in the autumn cold ...

•

Cobus Block is a Fulbright scholar now based in Kazakhstan. Also check out his previous entry for the Anthill, "Life is an Internet Cafe".