A commonplace book for digital times

Reinventing curation with a purpose, by Andrew Taggart

In a conversation I had with a journalist, we discussed what he deemed the two temptations of our post-print era. One is getting mixed up in the “information jungle”. The other is sitting complacently in a “filter bubble”. He suggested that the task of good curation in the coming years will be expose readers to, without overfeeding them on, information and ideas that challenge or deepen their firmly held beliefs. All right, but what shall we call it? How about “out-of-the-jungle, beyond-the-bubble journalism?”

It seems to me that, whatever it’s called, this style of curating is vital but also insufficient. It’s vital because it complexifies our understanding and compels us to re-examine our tendency to circle the wagons, engage in groupthink, and confirm our biases. But it’s insufficient inasmuch as it doesn’t seek to move us, in some stepping stone way, from lower to higher, from worse answers to better ones, from a fragmented picture of things to a more synoptic view of the whole.

The Latin word educare has the agrarian sense of “rearing” and “bringing up”. One task of curation, I submit, could be to lead us in a certain direction without pandering, bullying or nannying. That is neither hand-holding nor forcing your hand. It’s not florid rhetoric or hard-nosed criticism, both of which are concerned with getting us to admit the flaws in our arguments, to make up our minds, or to change our positions. Instead, it urges us to follow a certain line of thought, to strike out on a path and see where it takes us. From there, we would ask, “Does this bring us greater clarity about ourselves and our world?”

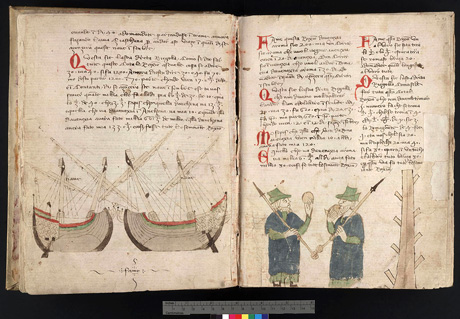

Assuming that this is worthwhile (and I think it is), I’m not entirely sure how to go about it. One possibility could be to reinvigorate the commonplace book tradition, with a twist. Commonplace books, popular from the Renaissance up through the 17th century, were scrapbooks of maxims, drawings, lists, inspirational quotations and marginal notes. By design, they were meant to be hodgepodge: a recipe here, a line from Horace there. In this serendipity there was exquisite beauty.

Think how many collages, mélanges, bric-a-bracs, shards and fragments are lying about us today online. I wonder whether we could retain something of the magic and surprise of the commonplace book but also order the bits and pieces so that they appear as if they were making an argument, giving us a more holistic way of seeing things, or leading us down a particular path to a better understanding. I wonder whether the parts can be gathered together into a synthetic whole.

I don’t know, but I’m dying to find out.

•

Andrew Taggart is a “philosophical counsellor, PhD”