Portrait of a Beijinger: Call of Duty (video)

A deli owner collects war relics in a bunker museum – by Tom Fearon

Each month, Tom Fearon and Abel Blanco profile an ordinary Beijinger with an extraordinary story. We’re proud to present the second episode in the series, along with Tom’s story of meeting its protagonist Yang Guoqing. The video is viewable on Youku for streamers in China, and on Vimeo as embedded below

The town of Nankou on the outskirts of Beijing is perhaps best known for its abandoned, incomplete amusement park Wonderland, a ghostly reminder of China’s property bubble. But beyond the fake Disneyland façade is a winding mountain road to a highland, overlooking the sleepy Ming Dynasty village of Changyucheng, that provided one of the most dramatic backdrops to the Second World War.

The windswept mountain is dissected by a 500 year-old section of the Great Wall, its decay and remoteness sparing it from the hordes of tourists lured further north to Badaling. The centuries have taken their toll on the wall, parts of which have been swallowed whole by the mountain. But more visible scars – bullet holes, some with rounds still embedded in the stone – remain in the watchtowers, nearly eighty years after they were caught in the crossfire of the Battle of Nankou between Japan and China.

A decade ago, local deli owner Yang Guoqing was camping at the highland site when he discovered bullet shells and other remnants of the battle. Despite being born and bred in Changping district nearby, he had never heard of the conflict that claimed the lives of around 15,000 Japanese and 6,000 Chinese troops.

Dressed in military fatigues with his trusty metal detector slung over his shoulder like a rifle, Yang has developed a spiritual connection with the area. The only shrine to the Battle of Nankou is a 150-kilogram marble tombstone he bought and carried up the mountain. Each time he visits to search for relics, he dutifully polishes the tombstone that stands on a bed of rocks scattered with empty baijiu bottles and cigarette packets, posthumous offerings to fallen soldiers.

“I’m not an expert on souls or a devout believer [in the afterlife],” Yang tells me, “but there have been a few times when I’ve been at the battlefield and felt a spiritual presence. Because it can’t be seen or understood, there is no way to verify it. But based on our tradition, I think a trace of our souls exists after death,” he says.

As we walk along the mountain path, Mr Yang drops without warning into a small trench nestled along the ridge. Lying on his stomach like a sniper, he pretends his metal detector is a gun as he explains how the summer vegetation provided ample cover to soldiers during the raging battle.

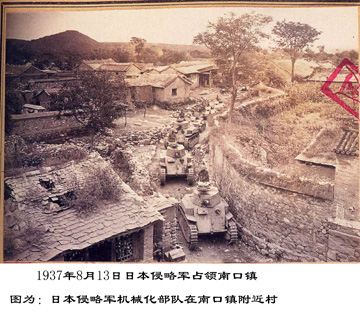

The Battle of Nankou was a flashpoint in Operation Chahar at the beginning of the Sino-Japanese war, August 1937. Having captured Beijing and Tianjin the month before, Japan sought to advance into coal-rich Northwest China. Nankou, a last line of defense against Mongolian invaders in ancient times, was all that stood in their way. The battle pitted around 70,000 Japanese soldiers against 60,000 Kuomintang (KMT) troops, but Japan’s superior firepower defeated their poorly equipped rivals in eighteen days.

After the war ended and the Communists seized power in 1949, KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek fled with his forces to Taiwan, taking about two million soldiers with him. But many KMT veterans, including those of the Battle of Nankou, remained on the Chinese mainland and discarded any reminders of their military service. They didn’t talk about the war, and their relatives didn’t ask about it. The shame of being on the “other side” of China’s civil war continued until as late until 2013, when the dwindling number of KMT veterans living in the mainland were finally granted welfare benefits.

Reluctance to acknowledge KMT service, coupled with the decades that have past since the Battle of Nankou, made it difficult for Yang to track down veterans of the battle, but his breakthrough came in 2008 when he met Gao Junfu. Yang escorted the former KMT private to the mountain, where he offered a salute to fallen comrades. Gao died a couple of years after the visit, aged 94.

At the back of Yang’s deli in Changping is a spiral staircase that leads to his basement. The dimly lit, musty space was a man cave before he turned it into a museum. There is a table with beers, a punching bag hanging from a rafter, and a pool table hidden beneath piles of history books and a hand-drawn map. Each of the red and blue arrows on the map mark engagements in the Battle of Nankou.

Around 3,000 relics are carefully displayed on cloth-lined shelves that look like they might collapse with a forceful sneeze. There are no glass cases, and visitors can hold items including military swords, canteens and bullets. Yang uses white gloves to handle more fragile items, including a KMT gas mask used during mustard gas attacks, a soldier’s bristleless toothbrush, and a helmet with bullet holes that hint darkly at its owner’s fate.

Most visitors to the museum are Chinese, but Ono Makoto is among a small group paying respects on the mountain for Qingming Festival this year. Although he doesn’t have any relatives who served in the Japanese army, the Shanghai-based IT worker said he respects the work Yang does as a volunteer to highlight the senselessness of war, rather than focus on its heroes or villains.

“He faces facts and reality for what they are,” says Ono, “and strives for peace in the future. I can clearly see how he tries to encourage others to share this vision. I could see it when we went up the mountain together and through his efforts as a volunteer.”

Text, interviewing and subtitles by Tom Fearon; cinematography and photos by Abel Blanco or provided by Yang Guoqing

Tom Fearon is a writer and editor who has lived in China since 2009. He worked in Chinese state media for many years, was a print journalist in Cambodia and Australia, and now works in communications at an international school

Abel Blanco is a videographer based in Beijing who formerly worked in broadcast media in Spain. You can see some of his other short films here

Watch the first episode of Portrait of a Beijinger, about a Peking opera performer with an unusual hobby away from the stage. To recommend a person to be profiled in the series, please contact Tom