It was 1989

The Tank Man in Beijing’s Military History Museum – by David Moser

I was in Beijing, and it was 1989. This fact did not seem at all remarkable to me at the time, of course. It was January, I was on the campus of Peking University, and there were no telltale signs that the coming spring would be such a momentous one, though in retrospect numerology provided an omen with the confluence of all those auspicious nines – 1919 for the May Fourth movement, 1949 for Liberation, even 1789 for the French Revolution.

There was, to be sure, something in the air – a feeling of seismic shift. Deng Xiaoping’s decade had unleashed a torrent of creative chaos, and students felt a growing sense of impatience and empowerment. I had heard accounts of a professor called Fang Lizhi who was openly talking about democratic reform to auditoriums full of college kids, and there had already been a brief wave of student demonstrations in Shanghai and Beijing, the rumblings of which could still be felt on the Peking University campus, known as Beida.

Bulletin boards at Beida’s sanjiaodi, the “triangle”, were overflowing with tattered pages of handwritten poetry and short essays filled with vague but passionate discontent. Late night arguments around beer bottle strewn tables were becoming more focused on the question “What’s wrong with China?”. The iconoclastic CCTV documentary River Elegy, which I had watched in my dorm room the year before, had opened for the first time a public debate about China’s past humiliations, and its path to the future.

Meanwhile, the economic reforms of the past decade had handed the students new possibilities. You could get rich, you could get liberated, or you could get out. It was probably no coincidence that the magical realism of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s novel One Hundred Years of Solitude was captivating the young intelligentsia of the time. There was a sense that the old order had become miraculously suspended in mid-air, awaiting a presto of transformation.

I was at Beida to work with translators on the Chinese edition of a book on artificial intelligence, and the graduate students in the group were preparing to go home for the spring festival holiday. I returned to the States for a few months, with plans to be back on campus in the autumn. When I said goodbye to my friends and colleagues and left China behind, none of us suspected that Beijing was about to explode.

As events in Tiananmen square began to unfold in April and May, I largely depended on the nascent US 24/7 TV news cycle for updates. I spent many sleepless nights with my ear glued to the shortwave radio, listening to Voice of America and the BBC. The information age had not yet arrived in China – there was no Internet, no mobile phones to speak of, and fax machines were a corporate luxury. Even landline phones in homes and work units were very rare. After the massacre in the early morning of June 4, I had no earthly way of knowing the fate of my Beida friends. So it was with great relief that, a few days after the crackdown, I began to receive, at all hours of the night, long-distance phone calls from Beijing. “Can your department issue a student visa to get me out?” “Do you have any contacts at the American embassy?” “Can you phone my relatives in California?” “How do you book a plane ticket?” And sometimes just, “Help.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I often had a better overview of what was happening in Beijing than they did. A chaotic stream of raw images and unprocessed information was coming out of China, and even those on the ground in Beijing were at a loss to make sense of it all. Certainly no one had seen the video of the “tank man”, which had been looping continuously on network news channels in the US. I remember watching the clip for the first time with both shock and familiarity. I knew that stretch of Chang’an boulevard quite well – a stone’s throw from the Beijing Hotel, near Wangfujing, just around the corner from the historic first Xinhua bookstore where my friends and I used to spend Saturday afternoons, sweaty from the two-hour bike ride from Beida.

The television images, mediated through the mind’s eye, contracted space and time in such a way that the distance between me and the tank man seemed less than if I had actually been in Beijing to witness it.

As the summer passed, and the world began to slowly absorb and understand what had happened, my assumption was that I would very likely not see the streets of Beijing for a very long time. I imagined the bureaucracy to be in a complete shambles, and I couldn’t imagine that in all the chaos a visa for a lowly visiting scholar would be approved. But my visa came through more effortlessly than it ever had, and I found myself back at Beida in late August, eating jianbing pancakes for breakfast and biking through the not-yet-demolished hutongs.

On the surface, Beijing looked virtually unchanged – yet it was a city suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome. Before, people had greeted me with smiles and insatiable curiosity about the outside world. Now, many of them were more concerned that the outside world know the truth about what had happened in their city. As I biked through familiar streets with Chinese friends, they would point to specific areas and intersections, and recount to me the events of the night of June 3rd. At the Muxidi strip along Chang’an boulevard, you could still see jagged lines of bullet holes along the outside walls of the apartment buildings.

And of course, I had to go back to see the square. Orville Schell once wrote that every time he returns to Beijing, he feels disoriented until he makes it to Tiananmen, the “hub of the Chinese nation.” That hub had now become a scar. Although no one was allowed in the square itself, there were rumours that you could still see traces of tank tracks on the paving stones, and even bullet holes on the Monument to the People’s Heroes. The entrance from Chang’an boulevard was heavily guarded, but the rest of the perimeter less so. A group of us tried to approach the square from the narrow streets on the south side of the Great Hall of the People, only to be shooed off by soldiers with assault rifles when we passed an imaginary line in the middle of the street.

We retreated to a familiar hangout, the first KFC restaurant in China, near Qianmen to the south of the square. My Chinese friends and I had gone there shortly after it first opened in 1987 – they were attracted to its foreign exoticism, and I wanted to experience the kitschy fascination of a Western chain in China. Now they sat there glumly for hours, conducting a verbal autopsy on the student movement, and asked me how they might get out of the country. One of them said he felt safer there, as if the American fast food restaurant might have some kind of extraterritoriality privilege. The police dragnets were slow and not computerised, and the main student leaders had mostly escaped, but there were plenty of people left behind, and they were plenty scared.

While in daily life the situation was very much on people’s minds, June 4th was eerily absent from the official broadcast and print media. In book stores were hastily-published tract pamphlets, with crude caricatures of the student leaders and titles such as The Real Truth about Liu Xiaobo. There had been a media campaign in the month after the massacre, the nightly news broadcast pushing the official version of the story, but by September the government had scrubbed the media clean of the event, just as the soldiers had scrubbed the square clean of traces of the protest.

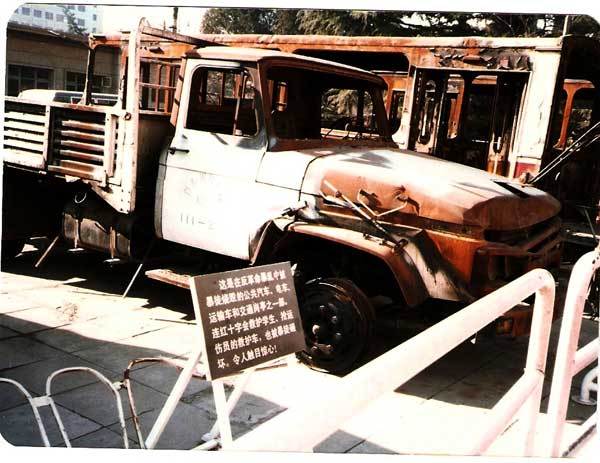

So my interest was piqued when in September I stumbled upon an exhibit at the Military History Museum honouring the soldiers who had crushed the protests in Beijing. Inside the main entrance were burnt-out tanks and rusted skeletons of military vehicles that had been torched by Molotov cocktails – each standing as proof of the misguided rage of the unruly mob. All of the plaques told the same tale, that a small group of “hooligans” (baotu 暴徒) and “people who don’t know the truth” (bu ming zhenxiang de ren 不明真相的人) had been duped by scurrilous foreign elements who had clouded people’s minds and instigated a “counter-revolutionary rebellion” (fangeming baoluan 反革命暴乱).

In a show of revolting callousness, one sign provided an itemized list of the number of vehicles burned by the demonstrators: 1000 military cars, 60 armoured vehicles, 30 police cars, and so on. Yet the authorities had not bothered to provide an estimate of the number of students and citizens who had died in the massacre.

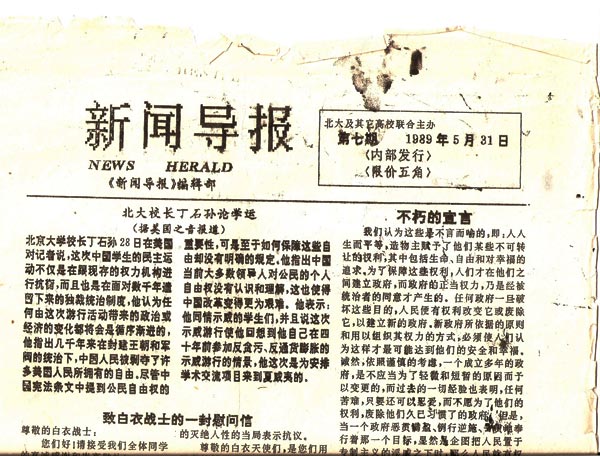

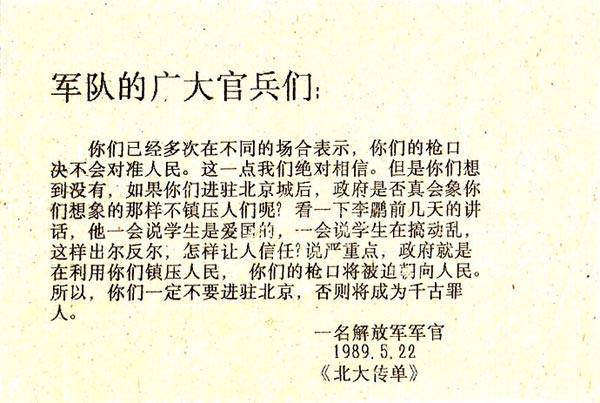

On display were weapons and clubs supposedly wielded by these hooligans against the military. There were gruesome, wall-sized photos of soldiers who had been disemboweled and burnt alive by the angry citizens. You could see the primitive mimeograph machine that the protesters had used to print flyers, announcements and the short-lived daily newspaper of the movement, the News Herald (Xinwen daobao 新闻导报).

Amazingly, some of Fang Lizhi’s articles were also on display, so that museum goers could see for themselves how Fang had poisoned the minds of young students with his political distortions and counter-revolutionary lies. I knew that Fang Lizhi was already in protective asylum in the US embassy, waiting for a diplomatic solution to allow him to leave China safely. I found it ironic that most Chinese had never read anything by Fang, but now, in the context of this state-sponsored exhibit, they would be exposed to his ideas for the first time.

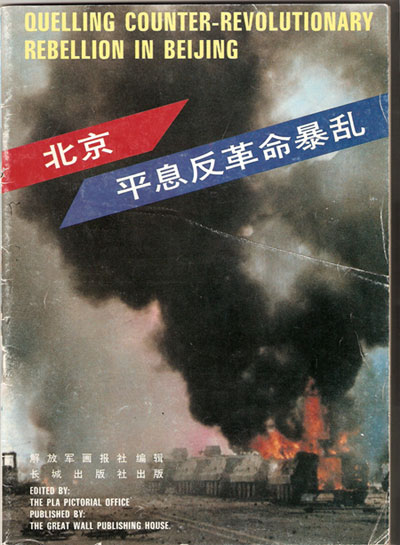

There were also several propaganda booklets on sale, in bilingual Chinese-Chinglish format, telling the government’s side of the story. I bought some of these along with an official government video, feeling a little guilty for giving money to the regime that had carried out the slaughter.

In the upstairs section of the exhibit, I turned a corner and found myself in a dimly-lit room where a grainy videotape loop was projected on the wall. It took me just a second to recognise it – the iconic “tank man” video. I nearly fell over. This was the last image I would have expected to see here. Why in the world would a state exhibit show the footage that had already become the most powerful symbol of the democracy movement? As I looked closer at the subtitles of the video, I understood the ploy:

Anyone with common sense can see that, if our armoured tanks had moved forward, would this brazen scoundrel blocking the tanks have been able to hold them back? The images recorded by the camera show that the truth runs counter to the propaganda of certain Western countries, and proves that our troops were exercising the utmost restraint.

In 1989 the word “spin” didn’t yet have the subtlety of meaning it does now, but this semiotic reversal was a truly outrageous example. I heard later that the video was even included in a 90 minute news documentary on CCTV as part of the attempt to massage the narrative, but the attempt was so clumsily obvious that they reverted to their usual information strategy: erasure and silence. Even inside China, the tank man had his 15 minutes of fame – or 15 seconds of fame – courtesy of the Communist Party itself.

That video was just one of many incongruous and mind-boggling images that emerged from the chaos of those early months. There is footage of a pajama-clad Wu’er Kaixi and his friends allowed impossible access to the Great Hall of the People, confronting, even scolding, Li Peng to his face. There are pictures of the Goddess of Democracy, the Statue of Liberty’s little sister, impudently thrusting her torch in Mao’s placid face. But the most universally resonant image is still that of the tank man, an anonymous everyman defying a seemingly endless row of tanks in a feat of chutzpah that has been broadcast throughout the planet – with the exception of one country – for the past 25 years.

•

David Moser holds a Master’s and a PhD in Chinese Studies from the University of Michigan, with a major in Chinese Linguistics and Philosophy. He was a visiting scholar at Peking University in 1987-89. Moser is currently Academic Director at CET Chinese Studies at Beijing Capital Normal University, an overseas study program for US college students, where he teaches courses in Chinese history and politics. He has worked at CCTV as a program advisor, translator, and host, and is active in Chinese media as a commentator. He also plays jazz piano with various jazz groups in Beijing

Below are some of the author's pictures from the exhibition:

A sign details the number of military and police vehicles destroyed by “counter-revolutionary hooligans”

The short lived newspaper of the Tiananmen Square student movement, the News Herald

A notice by an anonymous PLA officer, published by the student movement, pleaing for military restraint

The cover of a book published a state publisher to put forward the official narrative about the massacre